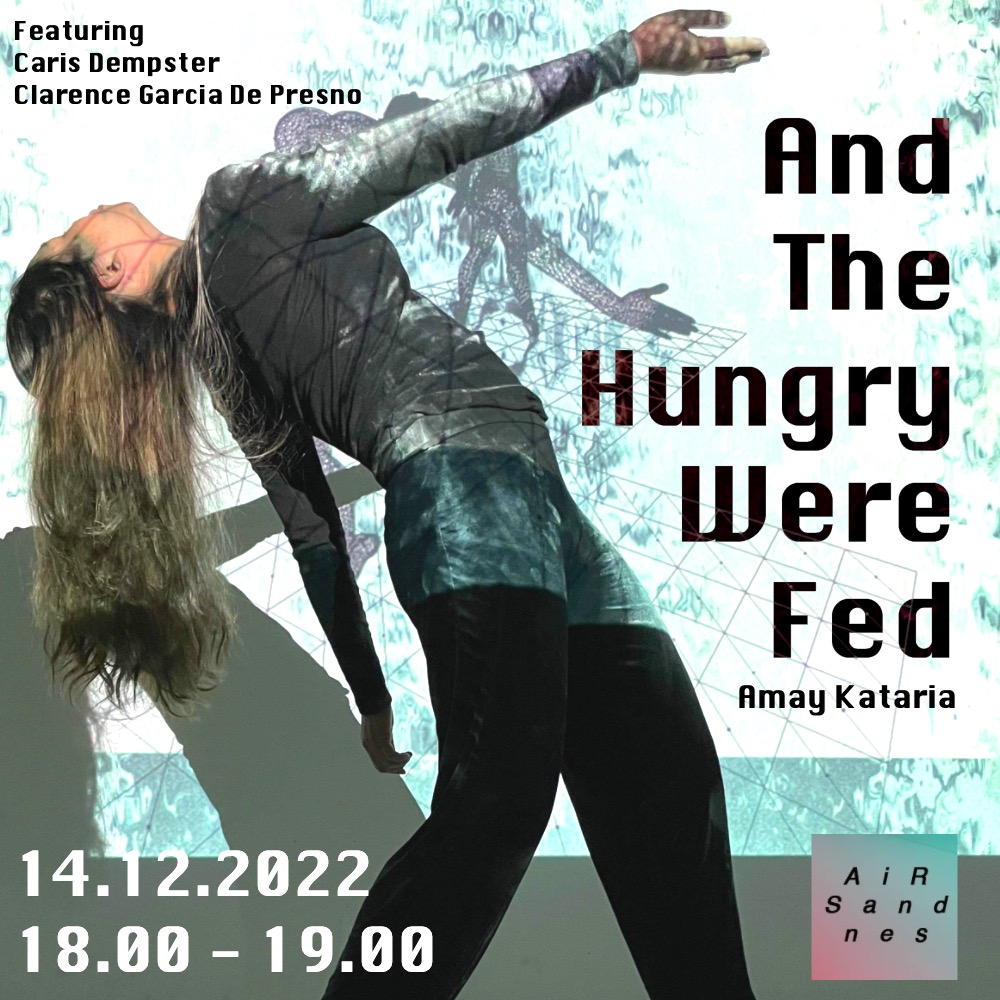

From November 10, 2022 to December 23, 2022, Amay Kataria was an Artist-in-Residence in Sandnes, Norway. And The Hungry Were Fed was his culminating show, which draws from an ancient ritual practice of kōlam-making from Southern India, where thousands of women routinely perform bodily gestures at dawn outside their homes, to draw ornate and traditionally abstract designs on the floor using a grid of dots as a reference. These inscriptions are crafted with rice flour, which becomes food for birds, insects, and nonhumans throughout the day, establishing a bond of reciprocity, offering, and kinship between humans and our significant others who make up this world.

In this interview with Nils-Thomas Økland from AIR Sandnes, Kataria dives into how this traditional practice inspired him to create an audio-visual performance.

Nils-Thomas: First of all, I would like to congratulate you for And The Hungry Were Fed – a successful exhibition and a performance while at AIR Sandnes. Could you briefly tell us a bit about this work that you created here?

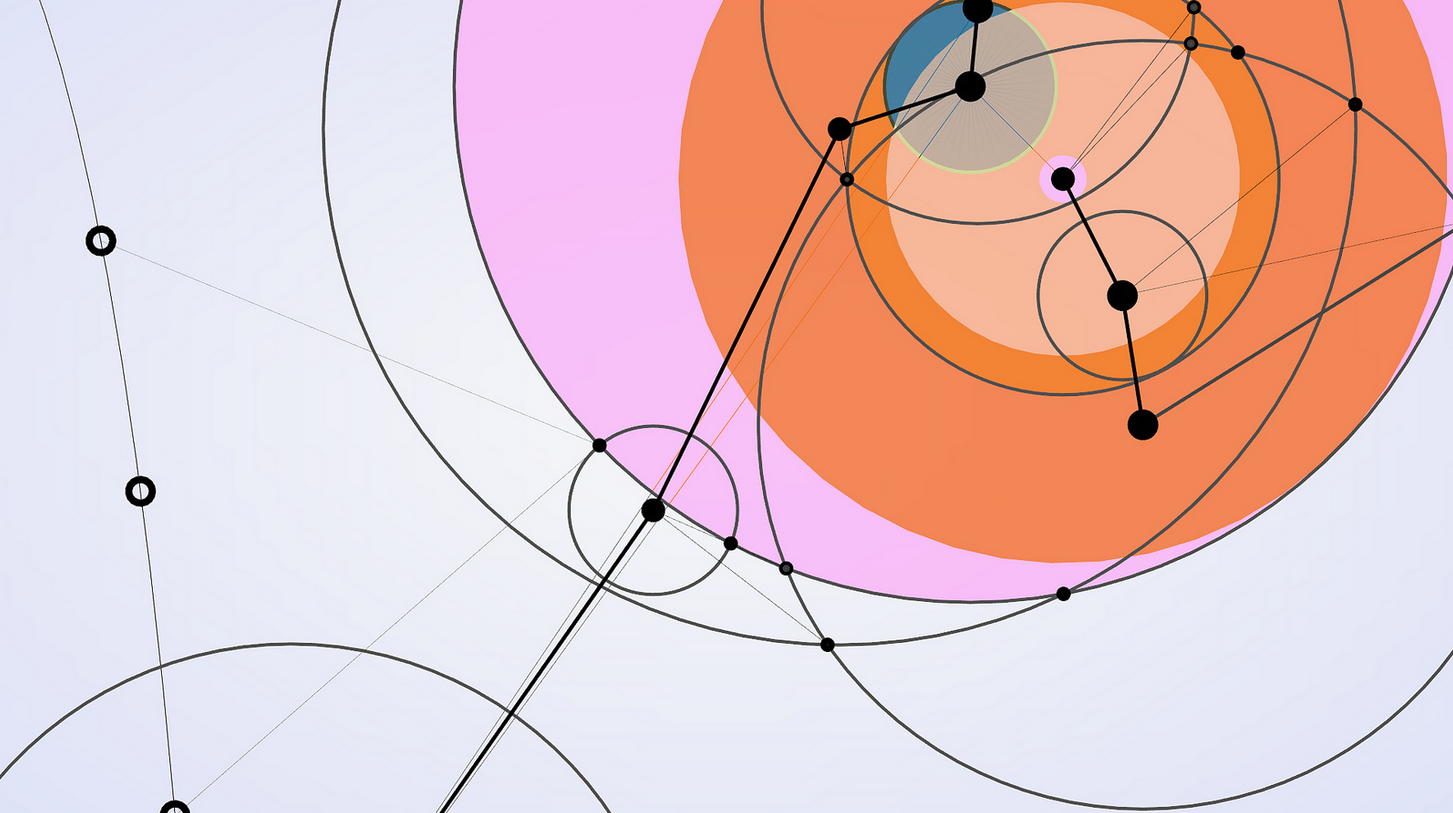

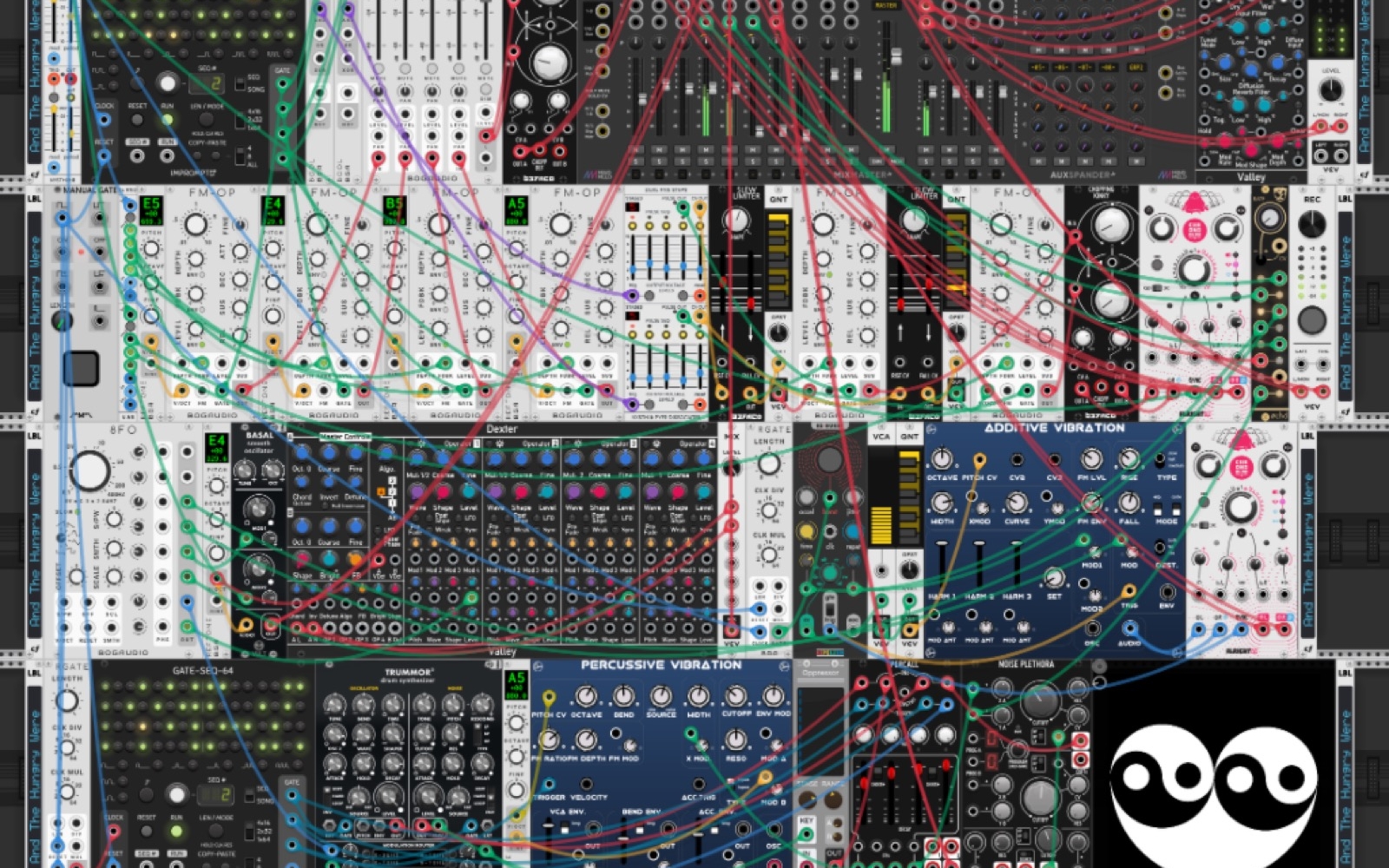

Amay Kataria: Thanks Nils-Thomas. The opening performance at the exhibition ran for about 20 minutes and consisted of three main elements. It began with looking for the right performers. Through an open-call organized by AIR Sandness, I found Caris and Claris, and began practicing with them in Stavanger, Norway every week. Secondly, the sound in the performance was very important because that’s what the performers were organically responding to. For every rehearsal, I iterated my digital audio synthesizer to calibrate the movements of the performers. Finally, the last element was the computer graphics that were projected on the wall, which made the backdrop of the performance. Through the residency, I developed an interactive video synthesizer, which combined several layers of visual content in real-time using a touch interface.

NT: You also had a grid of rice flour in the center, a series of smaller drawings and two big wall pieces made with thread. Even though they were a part of the whole, they had their own individuality. Having experienced the performance and the way you worked through the residency, these pieces appeared like tools that allowed you to manifest what happened in the performance. Is that something you can connect with?

AK: Absolutely, thanks for reminding me about those elements. Those artifacts fed into the main idea to create a cohesive exhibition space, which acted like a set for the performance. I developed those pieces to explore the subject of Kolams through multiple perspectives. I came to Sandnes to dive into Kolams and all these pieces were exploring the same idea through different mediums, but ultimately weaving an experience for the audience. When I began designing this set, I wanted to occupy the space in a meaningful way. In the center, I put a 4×4 grid made with rice flour that the performers interacted with, on the back wall were 16 8”x10” geometrical drawings, the two side walls were covered with thread woven around brass nails that I called wall-weavings, and the front wall had the projected visuals. Without the performers, I considered this set as an art installation in itself.

NT: You said you wanted to explore “Kolams” as an artist-in-residence. Could you talk about what that is?

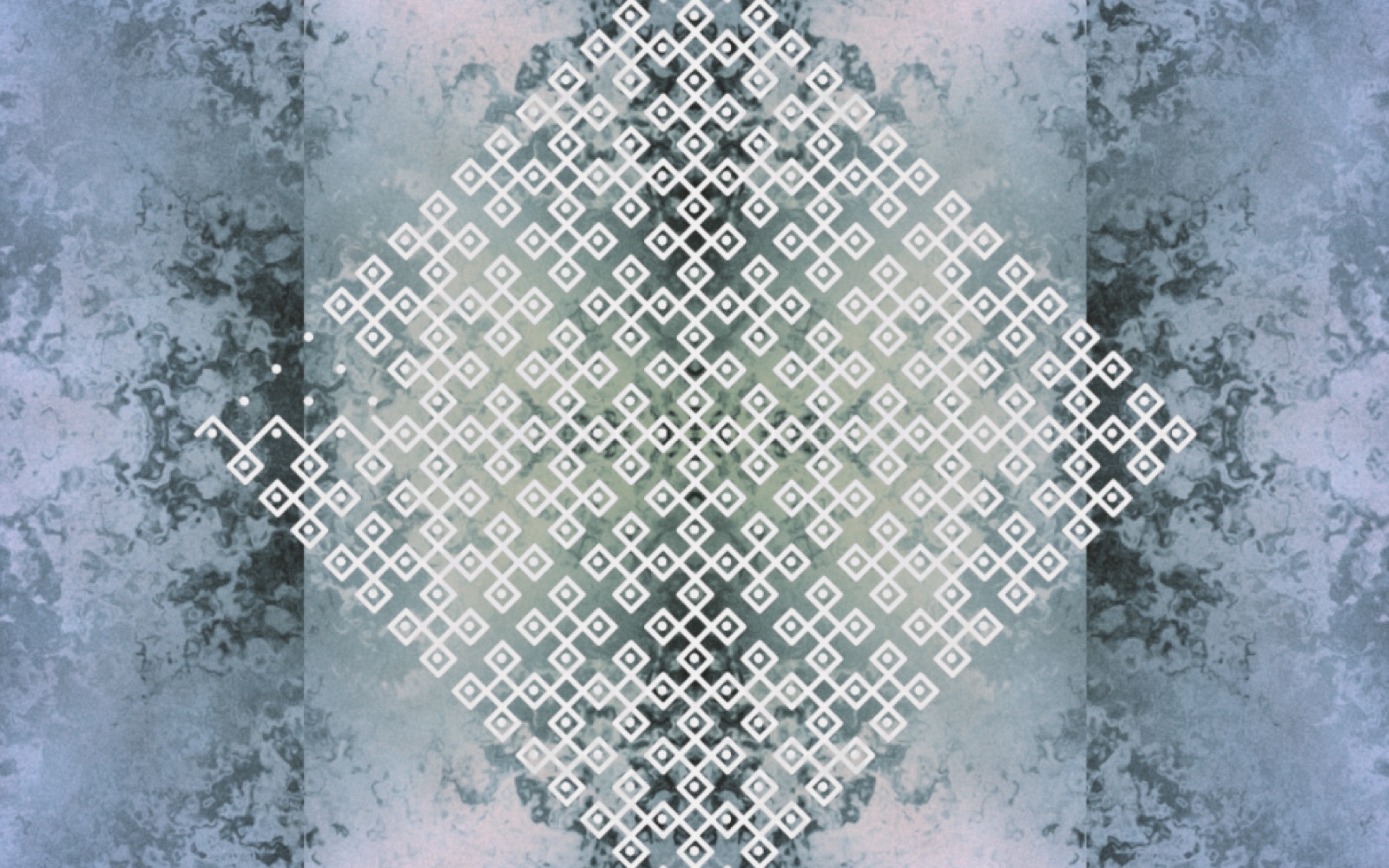

AK: Sure. A Kolam is an ornate design that is traditionally made by women in a state called Tamil Nadu in the southern part of India. It’s a ritual, where one would wake up early in the morning, and use rice flour to draw a pattern outside their homes as a gesture to welcome the new day. It has other symbolic meanings, for example, the rice flour acts like food for insects and critters throughout the day. Consequently, the Kolam deforms and changes itself with time until one cleans up the floor to create a new one the next morning. Thus, it’s ephemeral in its nature. Women who make these Kolams are passed this knowledge from their ancestors and regularly practice to improve their skills.

Due to its simple rules, there can be infinite possibilities of drawing a Kolam. I was really fascinated by them because of my engineering background and interest in computer graphics. What was surprising to me is that there has been a lot of research in western world about the mathematical and geometrical nature of these drawings. Scientists have tried to figure out how to teach computers to draw such patterns. Throughout the residency, I not only developed computer algorithms to draw the Kolams, but also abstracted a sublime performance from their visceral nature.

NT: It appears like you revisited your own culture in an entirely new environment during this residency. You also took over this traditional art space and transformed it from a white cube into a ritualistic setting. It wasn’t just about coming in and watching a performance in an exhibition space, but being part of something more than that. So, could you tell me a little bit about how you engaged with the actual space?

AK: From the beginning, I envisioned it as an alternative space to create an experience – perhaps a situation that unfolded in time. I wanted to create a space where people could walk into and get transported into a new realm. A sensorial world, where they’re bombarded with new information in an aesthetically pleasing way. You mention the performance being a ritual. What exactly is a ritual? It’s a set of practices that people do to feel at ease. It could be repeating a certain matra or performing an activity at a specific time. People perform these rituals to escape their daily routines and to find a space within themselves, which calms them, or gives them a sense of being connected. After spending hundreds of hours on this project during these past six weeks, I could synthesize an hour long experience, which acted like that escape. Perhaps, it was a manifestation of all the traditional, cultural, and mathematical resources that I was pulling from, to create a transformative space.

NT: But then you also have this very collaborative energy as part of your practice, where you are working with not only machines but also other humans. Thus, I think you were operating more as a director rather than an author. For example, to program the Kolams on your computer, you wrote a set of instructions, which had different parameters that controlled how the designs were getting created. Maybe you worked in a very similar way when creating this performative experience, where you made some sort of a framework for the performers to work in. As I understand it, you didn’t have a strict kind of choreography, but an open system that allowed the performers to bring something of their own to it.

AK: I really like the way you conceptualize that. In my practice, I spend a lot of time crafting procedures to be executed on a computer. Software, which is like soft memory for a machine, is like a set of rules developed to be executed in a systematic way. This autonomy gives the machine a sense of agency to make decisions on behalf of the computer programmer, who is not directly involved in those actions anymore. Randomness is built into those instructions, but obviously with boundaries that are predefined in the algorithms. This way of thinking can be attributed to early Fluxus performances by artists like John Cage, Nam June-Paik, and Alan Kaprow. While working with the performers for And The Hungry Were Fed, I created very loose rules for the movements, which had room for introducing improvisations. I would call it an open-closed system, which had a pre-defined prologue and an epilogue, but a very flexible story in between that unfolded in real-time.

That’s how I designed and performed the sound score as well. The sound system was created using a software called VCV Rack, which allowed me to create a digital audio synthesizer, made up of modules that were all patched together by passing digital signals to each other. These modules created an open-closed system, which could be massaged in real-time to create a sonic environment within a certain set of constraints.

NT: That’s really fascinating. Throughout the performance, the space was slowly transforming as the performers were picking up fragments of rice flour, creating new drawings with it, and sprawling it across the floor. Similarly with Kolams, you can keep a memory of the ornate design as a documentation; however, the next day one resets and starts fresh. How did you embrace this temporality and ephemerality within your work?

AK: The fundamental nature of reality is ephemeral. We are constantly changing. Every second, there’s something that’s dying within us and something that’s getting born. It’s just happening at a scale, which is not perceivable to us. Today, every art work is mediated through its documentation that we see on a screen, unless you actually get a chance to attend the exhibition. However, software art is slightly different from traditional media because it’s dematerialized in some capacity. Since it’s living inside a hard-drive, it manifests itself and demanifests itself on occasions. Its transient nature is something I’ve had to embrace very early on in my art practice.

Similarly, Kolams also undergo a transformation from their original form to a new form throughout the day. The nature of that transition is what I wanted to capture and exaggerate through the performance, where clean heaps of rice flour slowly changed into a pile of mess.

NT: I liked how the performance transformed the space. The initial space had piles of rice flour that made up the grid. And embedded within that, there was an action to construct something. The two performers initiated an act of movement and engagement with the rice flour, while constructing and destructing each other’s drawings through performative actions. And this was visible specifically towards the end when the energy in the space along with its physical representation had completely changed. The rhythm of the crowd had precipitated and the ritual had come to an end.

AK: I believe the rhythm of the space was set by the soundscape that I was performing. It guided the movements and the tension between the performers, who slowly destroyed these mounds of rice flour. According to traditional philosophy of Kolams, the dots represent the adversities in life. And the lines around them are the ways in which one navigates through these difficulties. It’s like a movement through a maze that we call life. Perhaps, in And The Hungry Were Fed, the performers directly faced these adversities by destroying these mounds of rice flour.

NT: Your work creates an interesting tension between the digital and the physical. For example, on one hand you developed computer graphics and on the other, there were tactile media like drawings on paper, wall-weavings, and the performance with rice flour. The projected image on the wall behind the performers had its own space, but felt like a continuation of the grid on the floor. Can you tell me a little bit about the interplay between these two worlds that you have created and how do they support each other?

AK: I initially began this residency program by developing algorithms for drawing Kolams on a screen. There are several ways to do it, but the method that I employed is called L-Systems, which is a drawing system made up of rules to create complex patterns by combining simpler forms repetitively. This process became the seed for the physical manifestation of the idea, which would allow the audience to tie the content on the screen with what was happening outside the screen. I was really drawn to that idea because it added a new dimension to the project, which not only had the potential to improve the experience, but also opened up a new territory to explore through performance.

NT: Do you see one as a tool for the other? Very often, we consider the digital computer a tool for us. It helps us understand something in the physical world. But for you, maybe physicality is also a tool for the digital, creating a feedback loop.AK: That’s a great observation. In my process, I often learn by drawing and writing things on paper. When I was developing the software to make Kolams, I had to learn how to draw a simple Kolam on paper first and break it down into smaller steps to teach a computer how to draw it. Thus, the physicality bled into the digital. And when that happened, I wondered how does somebody actually experience these Kolams in a more tactile way? So, there’s always a feedback loop. These boundaries are not really rigid anymore, but highly porous because ideas have the tendency to seamlessly travel between these worlds. In this exhibition, the computer graphics projected on the wall were feeding the context to the grid on the floor. The changing time and space in the digital world was in conversation with the performance that was happening outside the screen.

NT: But I didn’t perceive the moving image on the wall as a video. Time was definitely part of it, however, it seemed like it was generated only within the duration of the ritual from beginning till the end. I perceived it as a never-ending thing. Along with the Kolam patterns on the wall, you also blended other visual elements like human bodies and insects like ants chipping away on tiles. How did these things come across in your visual language for this work?

AK: During my research, I learned about another way to make Kolams by using tiles, which were made up of 6 basic shapes that are found in a Kolam. Just like a puzzle, one could arrange these tiles to create intricate and large scale designs. In fact, the workshop that I did at Sølvberget called Dots, Lines & Folklore, used tiles to teach young kids how to make a Kolam. For one of the visual sequences, I designed computer graphics to organically arrange the tiles on the screen and interactively modify them. For example, I could spawn ants that would go and eat those tiles, decaying the Kolam on the screen over time. I mentioned previously how the Kolams outside the homes provide rice flour to feed the insects and critters through the day. This builds a connection with the non-human other on a spiritual level. By using ants in the visuals, I’m didactically pointing out the act of making kin, excercising generosity, giving, and connecting with the world around us.

Additionally, the introduction of the human body in the visuals was very accidental. The idea originated when I started rehearsing with the performers to create a connection between what was happening in the physical and digital spaces. The two performers in the physical world were in a conversation with the two bodies in the digital world. Caris and Claris were mimicking the movements of the digital bodies throughout the performance to tie the two spaces together.

NT: By using the symbol of the ant, this ritual seems to point towards nurturing. The making of Kolam as an aesthetic tradition appears to be like an act of care for both the human body and its soul. Food becomes the medium through which this nurturing happens. Does this element reflect in your practice at all?

AK: Absolutely. I approach my subjects through an act of care. Empathy, care, and kindness are core elements of my practice. I think they are critical because to make art, one needs those things. Otherwise, it’s very hard to put that kind of time and effort into something. I can’t make art with a sense of revenge and animosity. In fact, I approach it with sensitivity towards the world, towards others, and towards myself. The subjects find me and I find them, which begins a creative affair. These acts of care are embedded in the DNA of my work. As long as it continues, I can keep making art.

NT: Great. So, what’s next for you?

AK: David Bowie once said, “I don’t know what is coming next, but whatever it is, it’s not going to be boring.” That’s what I would say.

NT: It’s been a real pleasure to have you at AIR Sandnes. Good luck with your upcoming projects and your trip back to Chicago.

And The Hungry Were Fed was developed by Amay Kataria at AIR Sandnes in Norway, with performances by Caris Dempster and Clarence Garcia De Presno. The residency was facilitated by Nils-Thomas Økland, Sandnes Kommune, and Stasjon K.

Amay Kataria (b. 1990) is a new-media artist, who leverages custom software, three-dimensional modeling, and network architecture as his mediums of construction to create performative systems that superimpose digital production onto an analog reality or vice-versa. He holds an MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and was previously a new-media resident at Art Center Nabi and Mana Contemporary. He has previously exhibited at Vector Festival, Hyde Park Art Center, Ars Electronica, Electromuseum, amongst others.

Nils-Thomas Økland (b. 1981) is best known for his sculptural approach to art making, putting the material first whether he is working with drawing, printmaking or in three-dimensional mediums. Økland received his BA (Hons) in Fine Art from Falmouth College of Art in the UK and lives and works in Sandnes, Norway. Økland’s work has been exhibited at The National Art Exhibition (Høstutstillingen) in Oslo, Prosjektrom Normanns in Stavanger and the Sandnes Art Society.