As you enter the Evil Media Distribution Centre you’re faced with a central seating arrangement of stacked palettes. Flanking either side of the ad-hoc settee are walls festooned with clipboards, some of which have a second clipboard positioned beneath cradling a sealed baggie with objects inside. Nestled inside one is a simple bimetallic strip, beside it a x-ray sheet. Stepping back you get an impression of a gallery rendered as an accountants ledger, rows and columns of curios and electronic esoterica. In all 66 items decorate the gallery, each one accompanied with a short text describing the item’s media affordances (all of which are available to read online), including written submissions from Usman Haque and Dan McQuillan, and entries from media art collectives Critical Art Ensemble, !Mediengruppe Bitnik, and the Open Systems Association. The Evil Media Distribution Centre (EDMC) is the work of YoHa (Matsuko Yokokoji and Graham Harwood), whose work we’ve previously admired on CAN), and is presently exhibited at ‘the Ruin’ exhibition in the New Institute Rotterdam.

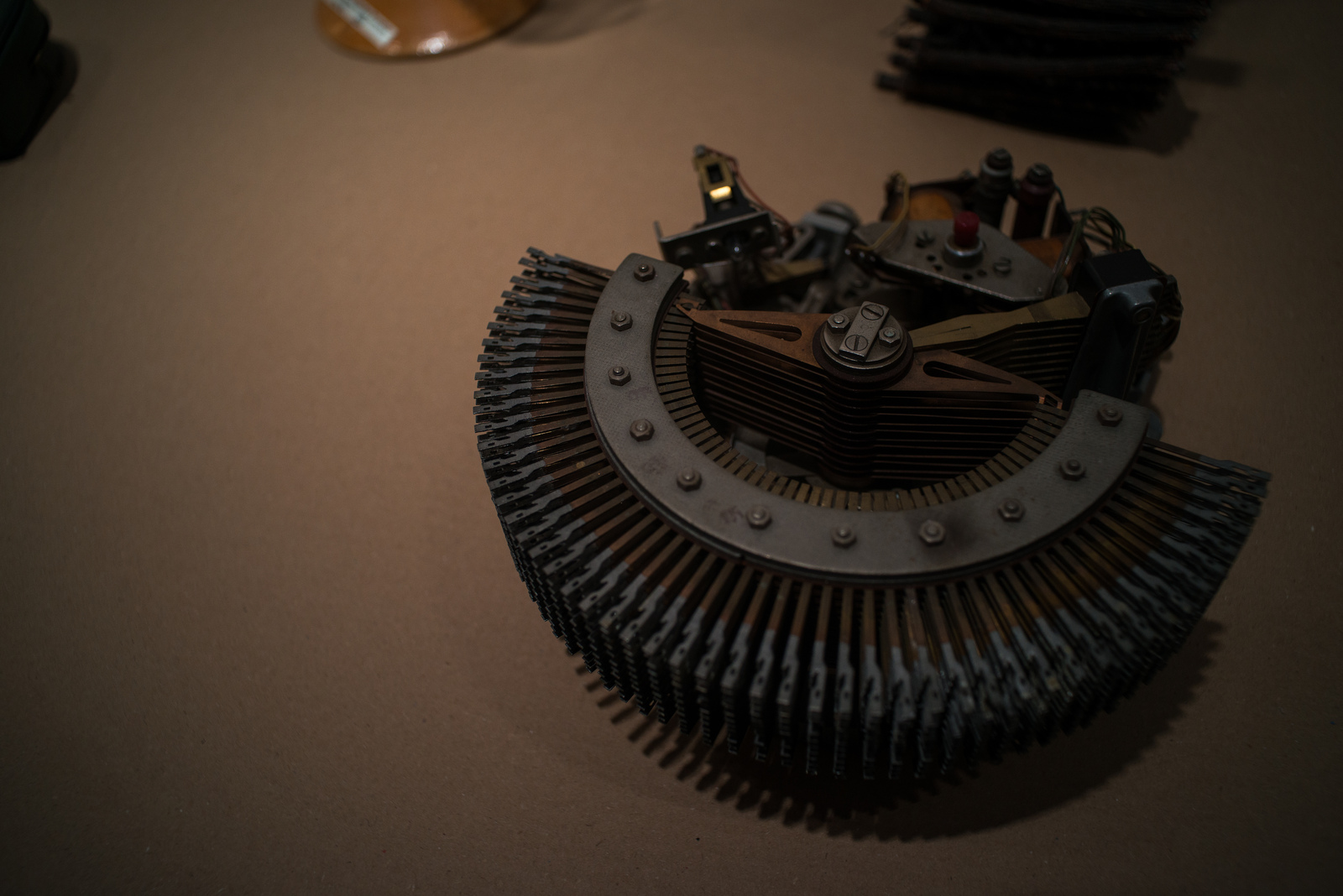

A photocopier, paper shredder, radio and rhoomba sit atop towers of pallets, each item’s origins detailed in 100 words or less. Considering the objects relations to one another brings media archeology to mind. Favoured by scholars of media art, media archeology is a method of observing our past and present technologies in parallel and with a detached perspective to get a “ clearer picture of what are present technologies are, what they do for us, what the say about our culture, hopes, desires, needs” (link). The media archaeologist is neither technologically deterministic nor does she naively champion the social shaping of our technology’s use. The Evil Media Distribution Centre has stacks of media archaeology, with digital milestones like the Hollerith Punch Card,7400 Series Shift Registers, Compiler/Interpreters, the ASCII character set all accounted for.

At this point its apparent that a different understanding of media than you might initially assume is in play. The Radio Wave, Strowger Telephone Switch and even the Sphygmograph (the first medical apparatus to make data visualisation of a patients pulse) can all be accommodated in our media theories. But what to make of the lone pedestrian barrier sullenly occupying the corner of the gallery?

The titular ‘Evil Media’ is derived in response to a book of the same name by Matthew Fuller and Andrew Goffey. That text reads like a “how to” guide to understanding the agency of technological systems. It coins the term “grey media”, referring to objects and processes which are imperceptible by dint of their banality and that influence the way we behave, think, and perceive. YoHa’s distribution centre is the nerve centre of grey media. Matthew Fuller says that:

We are looking at an expanded sense of media, as that which mediates. All objects and systems exist in an interplay of capacities and propensities that they exude and arise from.” A potent example of what Fuller is articulating is exposited by Lions’ Commentary on UNIX 6th Edition, with Source Code.

This was the last edition of Unix Source code whose documentation was permitted for classroom use before Bell Labs withdrew the license in 1979. Unixes ubiquity, and the potential for Linux, came about due to the intermingling of a magnanimous academic culture of sharing and the college photocopier (itself a grey media object!).

The origins of algorithms is dutifully excavated in this exhibition, and the many aspects that contribute to an algorithms existence and stabilisation are told in the grey media narratives. Alongside explanations of matrix manipulation and Hilbert space filling curves is a story of the world’s first business computer, and the Lyon’s Electronic Office (LEO) algorithm. Born of the Lyon’s & Co Tea Company, whose shops were “safe houses where liberated women could sit in the vicinity of strange men and eat cake”, the mercury memory and vacuum tube driven computer booted up on November 29th 1951 making an entire workforce of ‘human computers’ redundant. Elsewhere gloriously geeky levels of detail are indulged: the command line tool pTrace (“an active language, infiltrating and interrogating, snooping on and injecting code into living, running processes”) sits alongside short treatises of random numbers, and tales of the project MAC time sharing computer.

Befitting its expansive figuration of ‘media’ the EDMC is ambitious in the time-line chronicled: everything from the copper wire (9000BC) right up to the zero hour contract (2012 AD) are considered in terms of their mediating abilities (the latter being an interesting object to reflect on from Lawrence Lessigs ‘Code is Law’ argument). The media evolution of forms sketches their origins in antiquity, through to their use in statistics by John Gaunt, right up to contemporary HTML forms and their accompanying validation rules – “rudimentary software mechanisms for channeling potential user ambiguity into discrete data storage.” Sitting within that same genealogy are objects which are readily grasped as grey and dull; network diagrams, project management, logical frameworks, significance tests. The litany of dull objects, no matter what interesting note of trivia accompanies them, means that the mundanity of the objects can’t help but permeate your awareness the longer you stay in the Centre. This palpable banality is especially potent the longer you watch the looping video content (installed to represent the objects which lack an obvious physical presence – like the State Transition Diagrams). This is something which Graham Harwood is only too pleased to hear. “Boredom offers us a chance to reflect on the intimate glue in our lives. It’s the inverse of gadget glamour and for a society fatigued by spectacle it offers a particular relief.”

And yet when the painfully dull objects of today, like Social Media Analytics Tools, are considered in parallel with entities like the Stanley Milgram Postal Experiments – which, with the benefit of hindsight, are acknowledged as determining “that there is a pattern one can follow to understand social relations, and by which people can predict and engineer certain social phenomenon” – the weight of the grey media concept becomes apparent. Such informative juxtaposition is what YoHa aspired to: “The design of the work is easily digested a morsel at a time. We found that people understood each object but maybe had not read them together before.” You can appreciate why its important to not let grey media recede into opacity, to resist letting the junctures of software and hardware becoming obfuscated beneath seamless interfaces, as you regard the RAQS Media collectives consideration of the ink fingerpint. The gravity of a biometrics origin is brought into underlined when considered alongside the harrowing history of the Hollerith punch-card: “ throughout the 1930s IBM supplied Hitler’s regime with punch cards and tabulation equipment, ensuring that Jews could be traced and eliminated by the Nazis”.

Undergirding the whole exhibition is a palpable sense of how technical, abstracted and programmed systems move us and our surroundings in manners to which many of us are unaware. At the appreciable end of that spectrum are objects like the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Shipping Container Corner (yes, corner!) and Pallets (whose presence as object of utility and appreciation nicely riffs with the theme of grey media): physical objects that better engineer the mass movement of the goods that service our needs on a daily basis. The presence of the Oracle 11g relational database management system (RDBMS) and the genomic binary assignment map point towards the digital, abstracted, invisible, yet no less powerful, objects which orchestrate us as populations of consumers and ailing bodies. The pedestrian barrier no longer seems so aberrant an inclusion when you consider it as ambulatory technology with a banal, yet efficient, means to channel crowds of people and facilitate their navigation. It’s difficult to avoid inferring connections with Unpleasant Design and Risk Choreography (“the nature in which people and object maneuver in space and time in order to minimize impact of danger”) (link). Fuller is inclined to agree: “The artist David Rokeby says that surveillance cameras and sensor-actuator set-ups send algorithms out into space. But the question is how to play with, nurture or raise sensitivities to such qualities?” Fuller thinks the exhibition goes some way to answering the latter question:

An exhibition, that places one thing next to another, allows us to imagine kinds of proximity and affinity by watching the connections between things in themselves, in all their multivalence, rather than simply as they are described.

Evil Media Distribution Centre by YoHa, produced with Tom Keene & Anna Blumenkranz

Exhibition | NAI Rotterdam – Gallery 1 | 22/06/13-15/09/13

| Author: @stephenfortune Stephen is a media artist and writer. In the former pursuit his work is inspired by pidgin programming, cargo culting, and the tactical use of kludged contraptions. He is Tech editor at large for Dazed & Confused magazine, and divides his time between Dublin and London. http://www.stephenfortune.net/ |