Foreword by Ricardo Sanchez

Back in March I had the pleasure to attend Karsten’s workshop at the 2013 Resonate conference in Belgrade, in it we learned how to work with audio and music while coding live using the Clojure programming language. It was great! I got so addicted to this new way of programming that it made me work on a little tutorial so I can share my experience with newcomers. After I finished my first draft I asked Karsten to do a technical review of it and he very kindly accepted. A couple of weeks months later we managed to expand & transform it into a comprehensive introductory article to Clojure and functional programming with a few very cool examples I hope you’ll enjoy. Without Karsten’s input this tutorial would never have been what it is today – so for that a big THANKS is due to him and the Resonate team for putting together such an awesome event.

Foreword by Karsten Schmidt

Getting (back) into the magical world of Lisp had been on my to-do list for a long while, though my first encounter with Clojure in 2011 was through sheer coincidence (if you believe in such things!). It took me only a few hours to realise how this encounter was impeccable timing since there was this nagging feeling that I had become too accustomed to the status quo of the languages I’d been using for the last decade. Most importantly, I instinctively knew, I wanted to learn & use this language for my own work, badly & ASAP. And indeed, I’ve been fortunate enough to be able to use Clojure on several large projects since, from cloud based server apps/renderfarms to OpenGL/CL desktop apps and a festival identity. What I wasn’t quite prepared for were the many doors (of perception and inquiry) Clojure has opened wide in terms of process, thinking & learning about code from outside the boxes of our so beloved, popular languages & frameworks. Now, having been using it almost daily for 2.5 years, this tutorial, this labour of love, is largely meant to share some findings of this journey so far (though admittedly this first part is more of a crash course) – all in the hope to inspire some like-minded souls from this community, keen to help realising the untapped potential this language & its philosophy bring to the creative drafting table…

Since this tutorial has grown well beyond the scope of a single article and there’s no TL;DR version, we will be releasing it in stages over the coming weeks…

Introduction

This tutorial aims at giving you a taste of functional programming with Clojure, a modern dialect of Lisp designed to run as an hosted language on the Java Virtual Machine (and an increasing number of other host platforms). Based on the lambda calculus theory developed by Alonzo Church in 1930s, the family of functional languages has a long history and forms one of the major branches in the big tree of available programming languages today. Largely through developments in hardware and the increasing numbers of cores in CPU chip designs, as well as through the appearance of languages like Erlang, F#, Haskell, Scala & Clojure, the functional philosophy has been re-gaining traction in recent years, since it offers a solid and plausible approach to writing safe & scalable code on these modern hardware architectures. Core functional ideas are also slowly infiltrating long established bastions of the Kingdom of Nouns, i.e. through the inclusion of lambda expressions in both the latest versions of Java 8 and C++11. However, Clojure goes much further and its combined features (e.g. immutability, laziness, sequence abstractions, extensible protocols, multimethods, macros, async constructs, choice of concurrency primitives) make it an interesting choice for approaching data intensive or distributed applications with a fresh mindset around lightweight modelling.

Sections:

1. Getting to know Clojure

2. Setting up an environment

3. Hello world, Hello REPL!

4. Clojure syntax summarized

5. Symbols

6. Vars & namespaces

7. Functions

8. Metadata

9. Truthiness, conditionals & predicates

10. Data structures

11. Common data manipulation functions

12. Sequences

13. Looping, iteration & recursive processing

14. Common sequence processing functions

15. Destructuring

16. Further reading & references

Getting to know Clojure

Clojure is a young (first release in 2007) and opinionated language whose philosophy challenges/contrasts (just as much as Rich Hickey, Clojure’s author, does) some commonly accepted assumptions about programming and software design. It therefore requires some serious unlearning and rethinking for anyone who’s ever only programmed in Processing, Java, C++ etc. (JavaScript programmers will find some of the ideas more familiar though, since that language too was heavily influenced by older Lisp implementations). So even if after working through this tutorial series you decide Clojure isn’t for you, the new perspectives should provide you with some food for thought and useful knowledge to continue on your journey.

As a reward for taking on this learning curve, you’ll gain access to ideas and tools, which (not just in our opinion) should excite anyone interested in a more “creative” computing process: a truly interactive programming environment without a write/compile/run cycle and live coding & manipulation even of long running complex systems, a language, which by design, removes an entire class of possible bugs, a super active, helpful community of thousands of users/seekers – and at the very least it will give you some alternative insights to common programming problems, regardless your chosen language. With the JVM as its current main host platform and Clojure’s seamless Java interop features, you’ll have full access to that language’s humungous ecosystem of open source libraries, often in an easier way than Java itself. Clojure’s sister project ClojureScript is equally making headway in the JavaScript world and there’re a number of efforts underway to port Clojure to other platforms (incl. Android and native compilation via LLVM).

Clojure’s (and Lisp’s) syntax is a bit like Marmite: There’re probably as many people who love it as there’re who hate it, though in this case the objections are usually just caused by unfamiliarity. The seemingly large amount of parantheses present is one of the most immediately obvious and eye-grabbing aspects to any novice looking at Clojure/Lisp code. However, being a programming language, this a) is obviously by design, b) not strictly true, and c) is the result of stripping out most other syntax and special characters known from other languages: I.e. there’re no semicolons, no operator overloading, no curly brackets for defining scope etc. – even commas are optional and considered whitespace! All this leads to some concise, yet readable code and is further enhanced by the number of powerful algorithmic constructs the language offers.

Whereas in a C-like language a simple function/method definition looks like this:

// C

void greetings(char *fname, char *lname) {

printf("hello %s %s\n", fname, lname);

}

// C++

void greetings(const char *fname, const char *lname) {

std::cout << "hello " << fname << " " << lname << std::endl;

}

// Java

public void greetings(String fname, String lname) {

System.out.println("hello " + name);

}...in Clojure it is:

(defn greetings [fname lname]

(println "hello" fname lname))Calling this function then:

// C-style

greetings("Doctor", "Evil");

; Clojure

(greetings "Doctor" "Evil")Clojure's philosophy to syntax is pure minimalism and boils down to the understanding that every piece of source code, as in any programming language, is merely a definition of an executable tree structure. Writing Clojure is literally defining the nested branches of that tree (identified by brackets, also called S-expressions or sexp, short for symbolic expressions). Even after a short while, you'll find these brackets seem to become automatic and mentally disappear (especially when using an appropriate text editor w/ support for bracket matching, rainbow brackets and structural editing features).

Also because this tutorial is more of a crash course and limited in scope, we can only provide you with a basic overview of core language features. Throughout the tutorial you will find lots of links for further reading and a list of Clojure related books at the end. Now, without much further ado, let's dive in...

Setting up an environment

As with any programming language, we first need to ensure we've got some proper tooling in place, before we can begin our journey through unknown lands. Since Clojure is just a language and runtime environment, it doesn't have any specific requirements for editors and other useful tools. However, the Clojure community has developed and adopted a number of such tools, which make working with Clojure (even) more fun and the first one we introduce right away:

Leiningen

These days most software projects are using a large number of open source libraries, which themselves often have further dependencies of their own. To anyone having ever worked with a language with an active community, life without a package manager seems like pure hell, trying to manage & install dependencies manually. Leiningen is the de-facto build tool used by the Clojure community, with its name being an humorous take on Ant, the former de-facto build tool in the Java world. Lein calls itself a tool for "automating Clojure projects without setting your hair on fire". It's truly one of the easiest ways to get started with Clojure and is so much more than just a package manager, even though in this tutorial we'll be mainly using it as such. So please head over to the Leiningen website and follow the simple 3-step install procedure (or check your system package manager, e.g. Homebrew for OSX: brew install leiningen). Regardless, you'll need to have an existing Java installation (Java 6 or newer) on your machine, before installing Leiningen...

The Clojure community has developed integration plug-ins for several popular editors & IDEs and we will start working with one of them Counterclockwise in the next part of this tutorial. A list of other options can be found on the Clojuredoc website.

Hello world, Hello REPL!

As briefly mentioned in the beginning, Clojure provides us with a fully dynamic programming environment, called the REPL: The (R)ead, (E)valuate, (P)rint, (L)oop. The REPL reads input from the user, executes it, prints the result of the process, then rinse & repeat...

The "read" phase converts source code into a data structure (mostly a nested list of lists). During "evaluation" this data structure is first compiled into Java byte code and then executed by the JVM. So unlike some other dynamic languages running on the JVM (e.g. JRuby, Rhino), Clojure is a compiled language and in many cases can have similar performance characteristics as Java.

The REPL quickly becomes the main sketch pad and development tool for many Clojure users, a space in which complex code is slowly built up from small parts, which can be immediately tested and experimented with, providing an uninterrupted experience.

To start a REPL with leiningen, simply type lein repl on your command line and after a few moments, you should see a prompt like this:

$ lein repl

nREPL server started on port 51443

REPL-y 0.1.10

Clojure 1.5.1

Exit: Control+D or (exit) or (quit)

Commands: (user/help)

Docs: (doc function-name-here)

(find-doc "part-of-name-here")

Source: (source function-name-here)

(user/sourcery function-name-here)

Javadoc: (javadoc java-object-or-class-here)

Examples from clojuredocs.org: [clojuredocs or cdoc]

(user/clojuredocs name-here)

(user/clojuredocs "ns-here" "name-here")

user=> _Btw. The first time

leinis run, it will download Clojure and possibly a number of other files/libraries. This only happens once and all files are stored/cached in this folder~/.m2/repository. REPL startup time will always take a few seconds due to the JVM initializations needed, however a REPL usually doesn't need to be restarted often, so in practice isn't an huge issue.Should ever end up triggering an action which will make the REPL hang (e.g. trying to display an infinite sequence), you can press

Control+Cto cancel this action.If you don't want to (or can't) install Clojure/Leiningen, you can try out all of the examples in this part of the tutorial using the online REPL at Try Clojure.

As is traditional, our first piece of Clojure code should be (println "Hello World"). So please go ahead and type it at the prompt. Once you hit Enter, the (R)ead phase of the REPL begins, turning our entered text into a stream of symbols. Provided there're no errors, these symbols are then (E)valuated according to the rules of the language, followed by (P)rinting the result of that code and (L)oop giving us a new prompt for input.

user=> (println "Hello World")

Hello World

nil

user=> _Input -> Process -> Output

...is one of the fundamental concepts in programming, especially in functional programming. If you look closely, you might be wondering where that

nilcame from?nilis Clojure's equivalent ofnulland here indicates that ourprintlnactually didn't produce any computational result. In fact, the display of "Hello World" was simply a side-effect of executingprintln(by pushing that string to your system's output stream), but theprintlnfunction gave us no actual value back, which we might pass to another process. We will return to this important distinction later on when we'll talk about truthiness, predicates and pure functions.

Some other brief examples:

(+ 1 2)

; 3

(+ (+ 1 2) (+ 3 4))

; 10

(+ 1 2 3 4)

; 10Looks weird, huh? At least no more nil is to be seen (of course we expected some results from an addition), and maybe you can already spot a pattern:

- Operations seem to come first (this is called prefix notation) and

- it seems the number of parameters/arguments doesn't matter...

These are the kind of assumptions, you might make coming from an imperative programming background (Java/C etc.), where symbols like +, -, /, * or = actually are operators, basically symbols with pre-defined, hardcoded meanings and can only appear in certain places within the code. In Clojure however, there're no such operators and + is just defined as a standard function and that function accepts indeed a flexible number of params (as do all other basic math operators).

Clojure syntax summarized

The syntax of Clojure/Lisp boils down to just this one rule and any Clojure form has this overall structure (no exceptions!):

(function param1 param2 ... paramN)Note: Functions are processes and parameters (also called arguments) are their inputs. The number of params depends of course on the function, with some not requiring arguments at all.

The parentheses define the scope of an S-expression (technically a list, but also a branch in the tree of our program), with its first element interpreted as a function to call. An important thing to consider at this stage is that all the elements (incl. the first) of such an expression can be (and often are) results of other function calls.

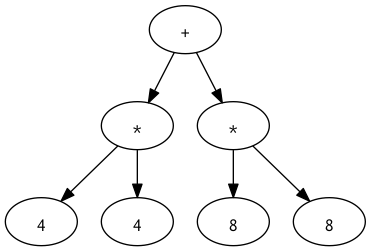

Here we calculate the sum of two products, the Pythagorean (c2 = a2 + b2) of a fixed triangle with sides a = 4 and b = 8:

(+ (* 4 4) (* 8 8))

; 80

The image shows a visualization of the encoded tree structure we've written. The tree needs to be evaluated from the bottom to the top: The inner forms (* 4 4) and (* 8 8) are evaluated first before their sum can be computed. Clojure is read inside out. At first this might seem alien, but really just takes getting used to and doesn't prove problematic in practice, since most Clojure functions are often less than 10 lines long.

Symbols

Symbols are used to name things and are at the heart of Clojure. Clojure code is evaluated as a tree of symbols, each of which can be bound to a value, but doesn't need to be. Of course in practice, it mostly means a symbol must have a bound value in order to work with it. Yet there're situations in Clojure when a symbol must remain unevaluated (as is) and we'll describe some of these in more detail when we discuss the list data type further below.

Imagine for a moment to be in Clojure's shoes and we have to evaluate the form (+ 1 2). The Reader simply provides us with a list of 3 symbols +, 1 and 2. The latter two are easily identified as numbers and need no further treatment. The + however is a symbol we don't know and therefore need to look up first to obtain its value. Since that symbol is part of the core language, we find out it's bound to a function and then can call it with 1 and 2 as its arguments. Once the function returns, we can replace the whole form (+ 1 2) with its result, the value 3. If this form was part of a larger form/computation, this result is then inserted back into it and the whole process repeats until all remaining forms & symbols have been resolved and a final value has been computed.

Symbols are conceptually similar to variables in that both provide reusable, named references to data (and code). Yet, variables don't really exist in Clojure. The biggest difference to variables in other languages, is that by default a symbol is bound to a fixed value once, after which it can't be changed. This concept is called...

Immutability

Immutability isn't a well known concept among the (imperative) languages, which readers of this blog might be more familiar with. In fact, these languages are mainly built around its opposite, mutability - the ability to define data, pass it around via references/pointers and then change it (usually impacting multiple places of the codebase). The fact, that immutable data is read-only once it's been defined, provides the key feature for truly enabling safe multi-threaded applications and simplifies other programming tasks (e.g. easy comparison of nested values, general testability and the ability to safely reason over a function's behaviour). The presence of immutable data also leads to fundamental questions about the actual need for key topics in object oriented programming, e.g. the need for hiding data through encapsulation and all the resulting complexity is only required if a language doesn't provide features protecting data from direct 3rd party (i.e. user code) manipulation. This problem simply doesn't exist in Clojure! On the other hand immutability too provides one of the most challenging unlearning tasks for people coming from a world of mutable state, since it seems paradoxical to work it into any realworld system requiring constant changes to our data.

Since no real application can exist without changing its internal state, throughout the course of this tutorial we will show how a) Clojure makes the most of immutability using persistent data structures, b) how actual mutable behaviour can be achieved where it is beneficial and c) show how mutable state can be easily avoided in most parts of a Clojure program. But for now please remember: Clojure data is immutable by default.

As an aside, unlike other functional languages like Haskell or Scheme where all data is truly 100% immutable and changing state can only be achieved through Closures & Monads, Clojure takes a more pragmatic route and provides a number of mutable data types. However, each of those is intended for certain usage scenarios and we will only discuss two of them (Vars and Atoms) further below.

Symbol bindings

In most programming languages variables are based on lexical scope: Depending on the level at which a variable has been declared in a program, its binding is either global or local (e.g. local within a function or class). Clojure also provides lexical scope binding using the let form, giving us local, symbolic value bindings only existing within its body.

The let form has this general structure and the last (often only) expression of its body becomes the final result:

(let [symbol value

symbol value ...]

body-expressions)Btw. The name

letcomes from mathematical texts, where we often say things like: "Let C be the sum of A and B" etc. To anyone with a previous career in BASIC, this should be familiar too...

Sticking with our pythagorean example from above, we could wrap the computation inside a let form and introduce two symbols a and b:

(let [a 4 ; bind symbol a to 4

b 8] ; bind symbol b to 8

(+ (* a a) (* b b))) ; use symbols

; 80

a ; outside the let form symbol a is undefined

CompilerException java.lang.RuntimeException: Unable to resolve symbol: a in this contextWe will deal with let several more times throughout this tutorial.

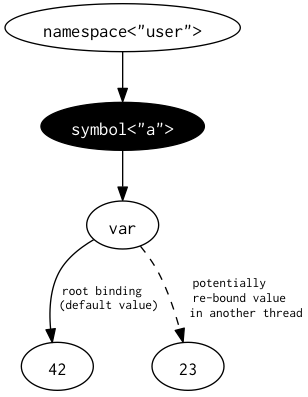

Vars & namespaces

Being restricted to only lexical scoped symbols defined with let is of course a painstaking way of programming, but thankfully isn't the whole truth. The basis of programming is "Don't repeat yourself" and that implies we need some form of mechanism to refer to existing values/processes defined elsewhere. In Clojure, this mechanism is implemented using Vars, named storage containers holding our data. Vars are named using symbols and can keep any datatype. They're always global within a given namespace, meaning they're visible from anywhere within that namespace and possibly others too.

Namespaces are an important concept (not only) in Clojure to manage modularity and avoid naming conflicts. They're conceptually similar to namespaces in C++, packages in Java or modules in Python, although in Clojure have additional dynamic features. All Clojure code is evaluated as namespaced symbols and the language provides a rich set of functions to create, link and manipulate them. You can read more about them on the Clojure website. In the REPL the prompt will always show which namespace we're currently working in (default user).

Back to Vars now, they're the closest thing to "traditional" variables in other languages, though are not equal: Whereas in many other languages a variable is a direct mapping from a named symbol to a value, in Clojure, symbols are mapped to Var objects, and only the Vars themselves provide a reference to their current values. This is an additional level of indirection, important for working in the dynamic environment of the REPL and in multi-threaded scenarios. For the latter, Vars provide a mechanism to be dynamically rebound to a new value on a per-thread basis and is one of Clojure's concurrency features we will discuss in a future part of this tutorial.

def is the general form used to define Vars. It is a special form which takes two arguments, but doesn't evaluate the first one and instead takes it literally to create a new Var of that name, which then holds the given value (if any). Vars can also be defined without a value, which keeps them initially unbound and is less common, but is sometimes needed to declare a Var for future reference.

We used Vars a couple of times already: the +, * and let symbols are all bound to Vars defined in the clojure.core namespace. But let's define two vars ourselves and then pass their values to a process:

(def a 4)

; #'user/a ; def returns the created var object

a ; just providing a Var's name will return its value

; 4

(def b 8)

; #'user/b

b

; 8

(+ (* a a) (* b b)) ; Vars used in a computation

; 80If we want to refer to a Var itself, rather than its value, we can use the

#'prefix or thevarfunction.

To explain some more how Vars are used in the light of immutability, let's look at another example: In imperative languages like C, Java, JS etc. we have the ++ operator to increment a variable by one. Clojure has the inc function: It too takes a value and returns the value + 1. So we can apply this to our a and see what happens:

(inc a) ; returns a + 1

; 5Correct answer. But printing out a shows its value is still 4...

a

; 4This is because inc does not operate on the Var a, but only is given a's current value 4. The value returned by inc is entirely distinct and our a is never touched (apart from reading its value).

Vars should only be used to define values in the interactive programming context of the REPL or for pre-defined values in Clojure source files. When we said that Vars are mutable, then this is only true in that they can be redefined with def (and some other advanced functions we won't cover here) to have new values, but practically, a Var should be considered unchangeable. Of course, one could write a function which uses def within its body to re-define a var with a new value, however this is considered non-idiomatic, generally bad form and is never seen in the wild. Just don't do it! If this is still confusing, we hope things will make more sense, once we've discussed Clojure's data structures and have seen how mutation of variables is actually not needed in practice.

Functions

In stark contrast to object oriented languages like Java, where classes and objects are the primary unit of computation, Clojure is a functional language with functions at its heart. They're "first class", standalone entities in this language and should be considered equal to any other type of data/value. They're accepted as arguments to other functions and can also be constructed or returned as result from a function call. With functions playing such a key role in Clojure, they can be defined in different ways and be given a name, but don't need to.

When defining a re-usable function, we most likely want to also give it a name so that we can easily refer to it again. To define a named function we use the built-in form defn (def's sibling and short for "define function") and provide it with all the important things needed: a name, a list of inputs (parameters) and the body of the function (the actual code). In pseudo-code this then looks like this:

(defn name [parameters] body-expressions)...applied to our above example this could be written like this:

(defn hypot

[a b]

(let [a (* a a)

b (* b b)

c (+ a b)]

(Math/sqrt c)))This implementation is not the most concise, but shows how we can use let to split up a computation into smaller steps and temporarily redefine symbols. We also make use of Java interop features to refer to Java's built-in Math class and compute the square root of that expression. According to Pythogoras, this is the actual length of the third side (the Hypotenuse) of the right-angled triangle given by a and b. A shorter alternative would be just this:

(defn hypot [a b] (Math/sqrt (+ (* a a) (* b b))))If you're coming from a C-style language, you might wonder where we define the actual result (or return value) of this function. In Clojure this is implicitly given: Just as with let, the result of the last expression in a function's path of execution is the result.

Now that we have defined our first function, we can call it like this:

(hypot 9 12) ; call fn with 9 & 12

; 15.0

(hypot a b) ; call fn with our Vars a=4 & b=8

; 8.94427190999916Anonymous functions

A function without a name is called an anonymous function. In this case they're defined via the special form fn, like this:

(fn [params] body-expressions)Just like defn, this form takes a number of parameter names and body expressions. So another alternative would be to use def and the fn form to achieve the same function definition as above (defn is really just a short form of this combo):

(def hypot (fn [a b] (Math/sqrt (+ (* a a) (* b b)))))Anonymous functions are often used with Cloure's data processing features (see further below), for callbacks or if the result of a function is another function, e.g. to pre-configure functions as explained next (readers with a JS background should also find the following familiar):

Let's take another brief look at the greetings function we showed at the beginning of this tutorial:

(defn greetings [name] (println "hello" name))Now, we assume such a greeting exists in other languages too, so we might want to define a German version as well:

(defn greetings-de [name] (println "hallo" name))The only difference between the two is the first part of the greeting, so a more reusable alternative would be to redefine greeting to use two arguments:

(defn greetings [hello name] (println hello name))

; #'user/greetings

(greetings "hello" "toxi")

; hello toxiThis is one of the situations where anonymous functions come into play, since we could define a make-greetings function which takes a single parameter (a greeting) and returns an anonymous function which then only requires a name, instead of a greeting and a name. Instead of using println we make use of the str function to concatenate values into a single string and return it as result.

(defn make-greetings

[hello]

(fn [name]

(str hello " " name "!"))) ; str concatenates stringsWith this in place, we can now define a couple of Vars holding such greeters for different languages and then use these directly:

(def greetings-es (make-greetings "Hola"))

(def greetings-de (make-greetings "Guten Tag,"))The new Vars greetings-es & greetings-de now contain the pre-configured functions returned by make-greetings and we can use them like this:

(greetings-es "Ricardo")

; "Hola Ricardo!"

(greetings-de "Toxi")

; "Guten Tag, Toxi!"We call functions which consume or produce functions Higher Order functions (HOF) and they play a crucial role in the functional programming world. HOFs like the one above are used to achieve a concept called Partial application and the mechanism enabling it is called a Closure, which should also explain Clojure's naming. We could also use the

partialfunction to achieve what we've done here manually.

Multiple arities & varargs

Even though this isn't the place to go into details just yet, Clojure allows functions to provide multiple implementations based on the number of arguments/parameters given. This features enables a function to adjust itself to different usage contexts and also supports functions with a flexible number of parameters (also called varargs, discussed at the end of this article).

Guards

Errors are an intrinsic aspect of programming, but taking a defensive stance can help catching many of them early on during the design stage, also articulated through the "Fail fast" philosophy popular amongst software folk. Clojure supports this form of Design-by-contract approach, allowing us to specify arbitrary guard expressions for our functions and uses them to pre-validate inputs (parameters) and/or the output (post-validation). E.g. we might want to constrain the parameter to our make-greetings function to only allow strings with less than 10 characters and ensures the function returns a string...

(defn make-greetings

[hello]

{:pre [(string? hello) (< (count hello) 10)] ; pre-validation guards

:post [(string? %)]} ; result validation

(fn [name]

(str hello " " name "!")))Guards are given as a Clojure map (discussed further below) with :pre/:post keys, each containing a vector of boolean-valued expressions (also discussed further below; in our case it's a call to string?, a so called predicate function, which only returns true if its argument is a string). Since the result of a function is an unnamed value, we use the % symbol to refer to it in the post-validatator. Attempting to call this guarded function with a non-string or too long greeting string will now result in an error even before the function executes:

(make-greetings nil)

; AssertionError Assert failed: (string? hello) ...

(make-greetings "Labas vakaras") ; apologies to Lithuanians...

; AssertionError Assert failed: (< (count hello) 10)Mr. Fogus and Ian Rumford have some further examples...

Metadata

Before moving on to more exciting topics, let's briefly mention some more optional features of functions: metadata, documentation & type hints. The following function is an extended version of our make-greetings fn with these all of these things included:

(defn make-greetings

"Takes a single argument (a greeting) and returns a fn which also

takes a single arg (a name). When the returned fn is

called, prints out a greeting message to stdout and returns nil."

[^String greeting]

(fn [^String name]

(str greeting " " name "!")))The string given between the function name and parameter list is a doc string and constitutes metadata added to the Var make-greetings defined by defn. Doc strings are defined for all built-in Clojure functions and generally can be read in the REPL using doc:

(doc make-greetings)

; ([greeting])

; Takes a single argument (a greeting) and returns a fn which also

; takes a single arg (a name). When the returned fn is called,

; prints out a greeting message to stdout and returns nil.Clojure allows arbitrary metadata to be added to any datatype and this data can be created, read and manipulated with functions like meta, with-meta and alter-meta. Please see the Clojure website for more information. E.g. to show us the complete metadata map for our make-greetings Var we can use:

(meta (var make-greetings))

; {:arglists ([greeting]),

; :ns #,

; :name make-greetings,

; :doc "Takes a single argument (a greeting)..."

; :line 1,

; :column 1,

; :file "/private/var/..."}Type hints attached to the function parameters were the other addition (and form of compiler metadata) used above. By specifying ^String we indicate to the compiler that the following argument is supposed to be a String. Specifying type hints is optional and is an advanced topic, but can be very important for performance critical code. Again, we will have to refer you to the Clojure website for further details.

Truthiness, conditionals & predicates

The concept of branching is one of the fundamental aspects in programming. Branching is required whenever we must make a decision at runtime based on some given fact and respond accordingly. In many programming languages, we use the Boolean values true and false to indicate the success or general "truth" value of something. These values exist in Clojure too, of course. However, in many places Clojure applies a more general term for what constitutes truth (or "success") and considers any value apart from false or nil as true. This includes any datatype!

As you might expect, the basic boolean logic operations in Clojure are and, or and not. The first two can take any number of arguments and each will be either truthy or not:

(or nil false true)

; true

(or 1 false) ; `or` bails at the first truthy value encountered

; 1

(and true nil false) ; `and` bails at the first falsy value encountered

; nil

(and true "foo") ; if all arguments are truthy, `and` returns the last

; "foo"

(not false)

; true

(not nil)

; true

(not 1)

; falseAn important aspect of and & or is that both are lazy, i.e. their arguments are only evaluated if any preceeding ones were falsy. Combined with Clojure's definition of truthiness and and/or returning not just boolean values, it's often possible avoid traditional branching in our code.

For the cases where we do need proper branching, we can use the if and when forms:

if takes a test expression and one or two body expressions of which only one will be executed based on the test result, in pseudo code:

(if test true-body-expression false-body-expression)...in real terms:

(def age 16)

(if (>= age 21)

"beer"

"lemonade")

; "lemonade"Being restricted to a single form for both the "truthy" and "falsy" branch is one important limitation of the if form, but is a reflection of Clojure's focus on using functions and an encouragement to limit side effects (i.e. I/O operations) to be only contained within functions. The second, falsy branch of if is also optional and if not needed, it is more idiomatic to use when instead. when is somewhat more flexible in these cases, since its body can contain any number of forms to be executed if the test succeeds:

(when (and (>= age 21) (< age 25))

(println "Are you sure you're 21?")

(println "Okay, here's your beer. Cheers!"))To achieve a similar effect using if we can either wrap these two println's in a function or use the do form, which is used as an invisible container for grouping (often side-effecting) actions and it returns the result of its last expression:

(do

(expression-1)

(expression-2)

...)Data structures

Data lies at the heart of any application, big or small. Apart from dealing with primitive data like individual numbers, characters and strings, one of the biggest differences between programming languages (and therefore one of the most important factors for choosing one language over another) is in the ways complex data can be defined and manipulated. As we will see next, this aspect is one of Clojure's highlights, as the language not only provides a rich set of primitives (incl. ratios, big integers, arbitrary precision decimals, unicode characters, regular expressions), but also truly powerful approaches to model & process data, of which we can unfortunately only outline some in the scope of this tutorial.

Before we discuss the various common data structures, we also need to point out once more that Clojure is an untyped, dynamic, yet compiled language. All of the following data structures can be fully recursive and contain any mixture of data types.

For reference, a full list of Clojure data structures is available on the Clojure Website

Lists

Lists are sequential data containers of multiple values and form the heart of Clojure (and Lisp in general). In fact, the name "Lisp" is short for List Processing. We actually already know by now how lists are defined, having done so many times in the previous sections: Lists can take any number of elements and are defined with ( and ) or using the function list. We also know by now that lists are usually evaluated as a function calls, so trying to define a list of only numbers will not work as expected:

(1 2 3 4)

; ClassCastException java.lang.Long cannot be cast to clojure.lang.IFnBecause the first element of our list is the number 1 (not a function!), Clojure will give us this error... Here's how & why:

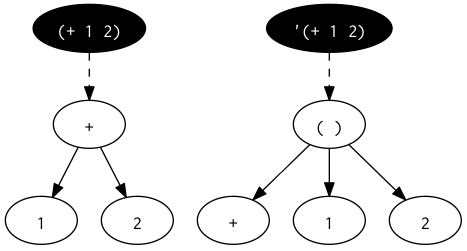

Homoiconicity

Long story short: In Clojure, code is data and data is (can be) code. Languages using the same data structures for code and data are called homoiconic and all Lisps share this feature, as well as other languages like R, XSLT, PostScript etc.

To treat code as data, we somehow need to circumvent the evaluation of our list as function call. To that purpose Clojure provides us with a quote mechanism to evaluate a data structure literally (as symbolic data). We can do this with any Clojure data structure to recursively stop evaluation of a form as code:

(quote (1 2 3 4))

; (1 2 3 4)

'(1 2 3 4) ; the apostrophe is a shorthand for `quote`

; (1 2 3 4)

'(+ 1 2)

; (+ 1 2)

(println "the result is" (+ 1 2))

; the result is 3

(println "the result of" '(+ 1 2) "is" (+ 1 2))

; the result of (+ 1 2) is 3The diagram below shows the impact of quoting and the difference of the resulting trees:

We could also use the list function to programatically assemble a list/function (using our previously defined vars a and b) and then evaluate it with eval:

; first construct a function call using a list of individually quoted symbols

(def a-plus-b (list '+ 'a 'b))

; #'user/a-plus-b

a-plus-b ; show resulting list

; (+ a b)

(eval a-plus-b) ; treat data as code: evaluate...

; 12

; treat code as data structure & look at the first item of that list

(first a-plus-b)

; # ; internal representation of `+` fn

; next treat code as data: replace all occurrences of a & b w/ their square values

; the {...} structure is a map of key => value pairs (discussed below):

; any keys found in the original list are replaced with their values

; so `a` is replaced with (* a a) and `b` with (* b b)

; the map is also quoted to avoid the evaluation of its contents

(replace '{a (* a a) b (* b b)} a-plus-b)

; (+ (* a a) (* b b))

; btw. if the map would *not* be quoted, it would be evaluated as:

{a (* a a) b (* b b)}

; {4 16, 8 64}

(eval (replace '{a (* a a) b (* b b)} a-plus-b)) ; data as code again...

; 80 We will discuss the

firstfunction in more detail below.

Right now, you might wonder why this is all worth pointing out. The most dramatic implication of homoiconicity is the enabling of metaprogramming, the programmatic generation & manipulation of code at run time and by doing this, being able to define our own language constructs. It also opens the door to lazy evaluation of code or skipping code entirely depending on context (e.g. what happens with and/or). Unlike C's pre-processor, which only operates on the original textual representation of the source code (before the compile step and hence is severely limited and potentially more error prone), Lisps give us full access to the actual data structures as they're consumed by the machine. For example this makes Clojure an ideal candidate for genetic programming or to implement your own domain specific language. The main forms responsible for these kinds of code transformations are macros and we will leave them for another tutorial...

Clojure lists have another important detail to know about: Because they're implemented as independent, linked elements, they can only be efficiently accessed at their head (the beginning of the list) and they don't provide direct, random access to any other elements. This restriction makes them less flexible than the next data structure, but still has some concrete use cases where this limitation doesn't matter: e.g. to implement stacks.

Vectors

Since lists in Clojure are both limited in terms of access and are semantically overloaded (as containers of code), it's often more convenient to use another similar data type to store multiple values: vectors. Vectors are literally defined using [ and ] or the vector function and are, like lists, a sequential data structure. We already encountered vectors when defining the parameters for our functions above, but just for kicks, here we define a vector with each element using a different data type: number, string, character & keyword (the latter is explained in more detail in the next section)

[1 "2" \3 :4]

; [1 "2" \3 :4]Like lists, vectors can contain any number of elements. Unlike lists, but very much like arrays and vectors in others languages, they can also be accessed randomly using an element index. This can be done in multiple ways:

(def v [1 2 3 4])

; #user/v

(get v 0) ; using the `get` function with index 0

; 1

(get v 10 -1) ; using `get` with a default value -1 for missing items

; -1

(v 0) ; using the vector itself as function with index 0 as param

; 1Maps & keywords

Maps are one of the most powerful data structures in Clojure and provide an associative mapping of key/value pairs. They're similar to HashMaps in Java or some aspects of JavaScript objects, however both keys and values can of course be of any data type (incl. nil, functions or maps themselves). The most common data type for map keys however, are keywords.

Keywords are simply symbols which evaluate to themselves (i.e. they have no other value attached). Within a given namespace only a single instance exists for each defined keyword. They can be created by prefixing a name with : or with the keyword function. Keywords can contain almost any character, but no spaces!

:my-key

; :my-key

(keyword (str "my-" "key")) ; kw built programmatically

; :my-keyBack to maps now. They are defined with { and } or the hash-map function (plus a few other variations we will skip here). Here's a map with 3 keys (:a :b :c), each having a different data type as its value (also note that :c's map uses strings as keys, much like JSON objects):

(def m {:a 23 :b [1 2 3] :c {"name" "toxi" "age" 38}})

; {:a 23 :b [1 2 3] :c {"name" "toxi" "age" 38}}Having defined a map structure, we can now lookup its values using keys. Once again many roads lead to Rome:

(m :a) ; use the map as function with :a as lookup key

; 23

(:b m) ; use key :b as function applied to m

; [1 2 3]

(get m :c) ; use get function with :c as key

; {"name" "toxi", "age" 38}

(:foo m) ; lookup a missing key returns nil

; nil

(get m :foo "nada") ; use get with default value for missing keys

; "nada"Note, we can use both maps & keywords as functions, because both implement Clojure's mechanism for function calls. Depending on context, it's good to have both as an option.

Since the values for :b and :c are nested data structures, we can continue this further...

((:b m) 2)

; 3

((:c m) "name")

; "toxi"Although this works, Clojure offers an alternative (nicer) approach, which becomes especially handy if our nesting increases: The get-in function allows us to specify a "path" (as vector) into our data structure to look up a nested value. As we saw already with get, this function can be applied to both vectors and maps (or a mixture of both):

(def db {:toxi {:name "Karsten"

:address {:city "London"}

:urls ["http://toxiclibs.org" "http://thi.ng"]}

:nardove {:name "Ricardo"

:urls ["http://nardove.com"]}})

(get-in db [:toxi :address :city])

; "London"

(get-in db [:nardove :address :city] "I think Bournemouth")

; "I think Bournemouth"

(get-in db [:nardove :urls 0])

; "http://nardove.com"select-keys can be used to extract a sub-set of keys from a map. The new map only contains the keys listed as arguments (if present in the map):

(select-keys m [:a :b :foo]) ; :foo isn't present in `m` so won't be in result...

; {:a 23 :b [1 2 3]}Sets

Sets are incredibly useful whenever we must deal with unique values, but don't care about their ordering. The name comes from Set theory in Mathematics. A Clojure set is (usually) unordered and will never contain more than a single instance of a given value. We will exploit this fact in the next part of the tutorial to build up our first full example application. Sets are defined like this:

#{1 2 3 4}

; #{1 2 3 4}

#{1 1 2 3 4}

; IllegalArgumentException Duplicate key: 1Be aware, that the literal definition syntax of sets doesn't allow duplicate values. However we can use it's functional equivalent:

(hash-set 1 1 2 3 4)

; #{1 2 3 4}...or we could use the set or into functions to convert another data structure into a set and hence filter out any duplicate values from the original (of course without destroying the original!):

(def lucky-numbers [1 2 3 4 4 2 1 3])

; #user/my-vals

(set lucky-numbers)

; #{1 2 3 4}

(into #{} lucky-numbers)

; #{1 2 3 4}

lucky-numbers

; [1 2 3 4 4 2 1 3]Since a set can be considered a special kind of map in which keys have no values, but are simply mapped to themselves, we can use the same lookup approaches to check if a value is present or not.

(get #{1 2 3 4} 3)

; 3

(#{1 2 3 4} 5)

; nil

(get #{1 2 3 4} 5 :nope)

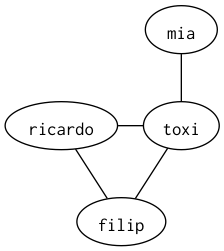

; :nopeAs a slightly more practical example, let's define a nested set of sets to encode the following mini social graph:

(def g

#{#{:toxi :ricardo}

#{:mia :toxi}

#{:filip :toxi}

#{:filip :ricardo}})Let's also define a simple lookup function (a predicate) to check if two people know each other:

(defn knows?

"Takes a graph and two node names, returns true if the graph contains

a relationship between the nodes (ignoring direction)"

[graph a b]

(not (nil? (graph #{a b}))))The

nil?function returns true if its given argument isnil.

Now we can use this function to get some answers (the order of names doesn't matter):

(knows? g :toxi :filip)

; true

(knows? g :ricardo :toxi)

; true

(knows? g :filip :mia)

; falseCommon data manipulation functions

Even in the face of immutability, what good is a data structure, if it can't be manipulated? One of the most often quoted and popular sayings amongst Clojurians is:

"It is better to have 100 functions operate on one data structure than 10 functions on 10 data structures."

-- Alan J. Perlis

It neatly sums up Clojure's approach to data processing and is achieved through a number of elegant abstraction mechanisms, allowing dozens of core language functions to work polymorphically with different types of data. Polymorphism allows for a very small, but powerful API and so reduces cognitive load for the programmer. Because each of the above mentioned data structures has its own peculiarities, the concrete behaviour of the functions discussed below slightly varies and adjusts to each data type.

Adding elements

Adding new data to existing collections is one of the most common programming tasks and in Clojure is usually done with conj.

For vectors, new elements are added to the end/tail:

(conj [1 2 3] 4 5 6)

; [1 2 3 4 5 6]For lists, new elements are added to the beginning/head (because it's most efficient), therefore resulting in the opposite value order:

(conj '(1 2 3) 4 5 6)

; (6 5 4 1 2 3)Maps are unordered collections and consist of key/value pairs. To add new pairs to a map, we need to define each as vector:

(conj {:a 1 :b 2} [:c 3] [:d 4])

; {:d 4, :c 3, :a 1, :b 2}Sets are also unordered and don't allow duplicates, so adding duplicate values will have no effect:

(conj #{1 2 3} 1 2 4 5) ; only 4 and 5 are added

; #{1 2 3 4 5}Another often used alternative exists for maps and vectors, both of which are associative collections: Maps associate keys with values. Vectors associate numeric indices with values. Therefore Clojure provides us with the assoc function to add new or replace existing associations (assoc too takes a flexible number of parameters so that more than one such association can be changed in one go):

(assoc {:a 23} :b 42 :a 88) ; override :a, add :b

; {:a 88 :b 42}

(assoc [1 2 3] 0 10, 3 40) ; override 1st element, add new one (comma is optional)

; [10 2 3 40]Important: For vectors you can only add new indices directly at the tail position. I.e. if a vector has 3 elements we can add a new value at position 3 (with indices starting at 0, this is actually the 4th element, therefore growing the vector by one). Attempting to assoc a greater index will result in an error, be careful:

(assoc [1 2 3] 10 -1)

; IndexOutOfBoundsException...Nested data manipulations

When dealing with nested structures we can use assoc-in and update-in to manipulate elements at any level. E.g. we might want to add Ricardo's current home town to our above mini DB map:

(assoc-in db [:nardove :address :city] "Bournemouth")

; {:toxi ......

; :nardove

; {:name "Ricardo",

; :urls ["http://nardove.com"],

; :address {:city "Bournemouth"}}}Like get-in, assoc-in takes a path into the datastructure and adds (or replaces) the value for that key. Whilst doing that it also creates any missing nesting levels automatically (i.e. :nardove's map did not even contain an :address key beforehand).

update-in is similar to assoc-in, however instead of a fixed value to be inserted into the collection, it takes a function (incl. any additional params) which is being applied to the current value for the key and then uses the result of that function as the new value. E.g. here we use update-in and conj to add another URL to :toxi's DB entry:

(update-in db [:toxi :urls] conj "http://toxi.co.uk")

; {:toxi

; {:name "Karsten",

; :urls ["http://toxiclibs.org" "http://thi.ng" "http://toxi.co.uk"],

; :address {:city "London"}} ....Removing elements

To remove items from a collection, we can use dissoc (for maps) or disj (disjoin) for sets. If a key to be removed isn't present, both functions have no effect.

(dissoc {:a 23 :b 42} :b)

; {:a 23}

(disj #{10 20 30} 20)

; #{10 30}Lists and vectors only allow for the direct removal near the head or tail, but don't support removing random items: pop applied to a list removes the first item, for vectors the last item. If the collection is empty, pop will throw an exception.

(pop '(1 2 3))

; (2 3)

(pop [1 2 3])

; [1 2]Immutability, one more time

We've just seen how we can add & remove elements from collections, thus seemingly modifying them - which technically would make them mutable, not immutable. However, as we've seen earlier, the modified results returned by these functions are not the original collections. To clarify:

(def v [1 2 3 4])

; #'user/v

(def v2 (conj v 5))

; #'user/v2

v2

; [1 2 3 4 5]

v

; [1 2 3 4]Our original v still exists even though we've added 5 to it! Under the hood Clojure has created a new data structure (bound to v2) which is the original collection v with 5 added. Thinking like a programmer, your next questions should be immediately: Isn't that incredibly inefficient? What happens if I want to add a value to a vector with 10 million elements? Doesn't it become super slow & memory hungry to copy all of them each time? The short answer is: No. And here's why:

Persistent data structures

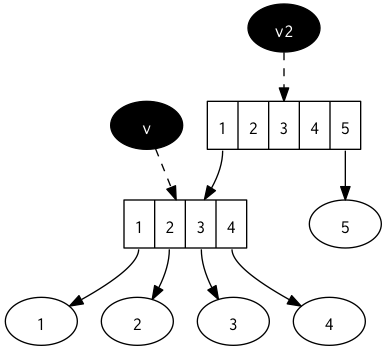

All Clojure data structures are so called persistent data structures (largely based on the paper by Chris Okasaki). Internally they're implemented as a tree and therefore can easily provide structural sharing without the need to copy data, which would be the naive solution to achieve immutability. The following diagram illustrates what happens internally for the above example:

Using trees as the internal data structure, our v2 can share the original contents of v and simply add a new leaf to its tree, pointing to the added value 5. This is very cheap and doesn't cause a huge loss of performance, regardless of the size of the collection. The same principle is applied to all of the mentioned data structures and it's this uniform approach which both enables & requires immutability.

Sequences

This section discusses Clojure's uniform approach to data processing using sequence abstractions. A sequence is a logical view of a data structure. All Clojure data structures can be treated as sequences, but the concept is extended even further and Clojure sequences include Java collections, strings, streams, directory structures and XML trees etc. You can even build your own ones by implementing an interface. The name for sequences in Clojure is seq and any compatible data structure can be explicitly turned into a seq using the function with the same name.

The sequence API

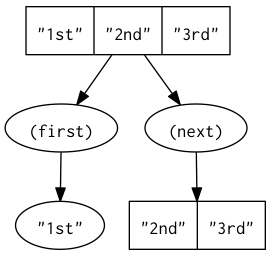

The sequence API is a minimal, low level interface consisting largely of only these four functions: first, next to read and cons & seq to create sequences. All of the following functions are built on top of these, but before we get there let's first illustrate their role using a vector and a hash map as an example:

(def my-vec ["1st" "2nd" "3rd"])

(def my-map {:a "1st" :b "2nd" :c "3rd"})Any Clojure collection can be turned into a seq, using the seq function. If the original collection is empty, seq will return nil.

(seq my-vec)

; ("1st" "2nd" "3rd)

(seq my-map)

; ([:a "1st"] [:c "3rd"] [:b "2nd"])

(seq "creativeapplications.net") ; a string's seq is its characters

; (\c \r \e \a \t \i \v \e \a \p \p \l \i \c \a \t \i \o \n \s \. \n \e \t)

(seq [])

; nilSince a map consists of key/value pairs, a map's seq is a seq of its pairs (vectors of 2 elements). And since a map is an unordered collection, the order of elements in its seq is undefined...

first

...returns the first element of a seq (or nil if the sequence is empty):

(first my-vec)

; "1st"

(first my-map)

; [:a "1st"]

(first "hello") ; a string can be turned into a seq as well...

; \h

(first []) ; first of an empty vector/seq returns nil

; nilnext & rest

As you might have guessed already, next returns a seq of all the remaining elements, excluding the first one. Again, if there're no further elements in the seq, next also returns nil.

(next my-vec)

; ("2nd" "3rd")

(next my-map)

; ([:c "3rd"] [:b "2nd"])We could now also combine the use of first and next to retrieve other elements, e.g. the 2nd element is the first element of the seq returned by next:

(first (next my-vec))

; "2nd"

(first (next (next my-vec)))

; "3rd"rest is almost identical to next, however will always return a seq: If there're no more elements, it will simply return an empty seq instead of nil.

cons

This function is used to prepend elements to a seq. cons takes two arguments, a value and an existing seq (or seqable collection) and adds that value at the front. If nil is given as the 2nd argument, a new seq is produced:

(cons 1 nil)

; (1)

(cons 2 (cons 1 nil))

; (2 1)

(cons \c "ab")

; (\c \a \b)Looping, iteration & recursive processing

At this point you might be wondering what use these above functions have in practice. Since Clojure offers far more high-level approaches to work with data collections, direct use of these functions in Clojure is actually less common. Yet, before we discuss these higher level functions, please bear with us as we want to illustrate some other important core operations common to all programming languages, one to which Clojure adds its own twist (again): Iteration & recursion. Meet the loop construct.

loop & recur

loop defines a body of code which can be executed repeatedly, e.g. to iterate over the elements of a sequence. This is best illustrated by an example, a loop which takes a vector and produces a seq of the vector's elements in reverse order (Clojure actually provides the reverse function to do the same for us, but we're focussed on loop here):

(loop [result nil, coll [1 2 3 4]]

(if (seq coll)

(let [x (first coll)]

(recur (cons x result) (rest coll)))

; no more elements, just return result...

result))

; (4 3 2 1)The vector following the loop keyword is a binding vector just as we know from let and it can be used to bind any number of symbols. In our case we only require two: the initially non-existing result sequence (set to nil) and coll, a vector of numbers to be processed. The other code is the loop's body which is executed repeatedly: At each iteration we first check if our coll contains any more elements by calling seq (remember, seq returns nil (and is therefore falsy) when given an empty collection). If there're any elements remaining, we bind coll's first element to x. What follows next is a call to recur, the actual mechanism to trigger the recursive re-execution of the loop, however each time with new values given for the loop's result and coll symbols. These new values are the updated result sequence (with x prepended) and the remainder of the current collection produced via rest. Once rest returns an empty seq, the loop is finished and result is "returned" as final value.

The combined application of loop & recur is the most low-level and verbose construct to create iterative behavior in Clojure, but because of that is also the most flexible. The most important restriction however is that recur can only be used at the end (tail) of a loop's execution path, meaning there can be no further expressions following recur (hence the concept is called Tail recursion. In the above example you might think the final occurance of result violates this restriction, but that is not true: recur is the last expression of the "truth branch" of the enclosing if, whereas the returned result is on its other branch and therefore independent.

doseq

A more concise way of completely iterating the elements of a collection is offered by doseq, however this form is designed to work with/trigger side effects and only returns nil. The example iterates over a vector of hashmaps and displays each person's age with some extra formatting:

(doseq [p [{:name "Ben" :age 42} {:name "Alex"} {:name "Boris" :age 26}]]

(let [name (:name p)

suffix (if (#{\s \x} (last name)) "'" "'s")

age (or (:age p) "rather not say")]

(println (str name suffix " age: " age))))

; Ben's age: 42

; Alex' age: rather not say

; Boris' age: 26

; nilThe value of suffix is based on the last letter of a person's name and is usually 's (unless the last letter is in the set #{\s \x}). We'd also like the :age to be optional and provide a default value if missing...

dotimes

dotimes is yet another looping construct used for side effects, this time just for simply binding a symbol to a number of iterations:

(dotimes [i 3] (println i))

; 0

; 1

; 2Common sequence processing functions

Now that we've discussed some of the underlying forms and mechanisms, it's time to focus on the more commonly used features of Clojure's sequence processing.

Loops and iterators are the de-facto tools/patterns to process collections in many imperative languages. This is where idiomatic Clojure probably differs the most, since its functional approach is more focused on the transformation of sequences using a combination of higher order functions and so called:

Pure functions

A pure function's does not depend on any other data than its inputs and causes no side effects (i.e. I/O operations). This makes them referentially transparent, meaning a function could be replaced with its result without any impact, or in other words, a function is consistently providing the same value, given the same inputs. Pure functions can also be idempotent, meaning a function, if applied multiple times, has no other effects than applying it once. E.g. (Math/abs -1) will always provide 1 as a result and (Math/abs (Math/abs -1)) will not change it, nor will it cause any other effect.

Pure functions play a key role in functional programming. Their characteristics allow us to compose small, primitive functions into more complex constructs with predictable behaviors.

Memoization of pure functions

The caching of results of previous calls to a function is called memoization. This technique is especially useful if these results are produced by a complex/slow process. Clojure provides the memoize HOF to allow any function be memoized, however safe memoization requires those functions to be pure. We can demonstrate this caching effect by simulating a slow function using Java interop and Thread/sleep:

; simulate long process by sleeping for x * 1000 milliseconds

(defn slow-fn [x] (Thread/sleep (* x 1000)) x)

(def not-so-slow-fn (memoize slow-fn))

(not-so-slow-fn 3)

; 3 <-- takes 3 seconds the first time

(not-so-slow-fn 3)

; 3 <-- immediate (cached) resultMap-Reduce

Several years ago, Google published a paper about their use of the Map-Reduce algorithm. Whereas this paper was focused on the distributed application of that algorithm running in parallel on thousands of machines, the general approach itself has been around for decades and plays an important role in many functional languages, where it is the de-facto pattern to process data without the need for explicit loops.

The idea of Map-Reduce is to first transform the elements of an input collection into an intermediate new collection of values, which is then passed to a reduction function, producing a single final result value. This result could be any data type, though, incl. a new collection.

Even though Map-Reduce is a 2-phase process, each phase can also be applied on its own. I.e. sometimes there's no need for a later reduction or an initial mapping step.

Btw. Several modern "NoSQL" database systems (e.g. CouchDB, MongoDB, Riak) and distributed data processing platforms like Hadoop also heavily rely on Map-Reduce as underlying mechanism to process & create views of data. So if you ever intent to work with such, it's quite useful knowledge to work through this section, even if you have no further interest in Clojure...

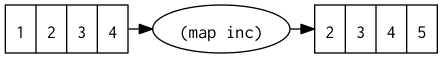

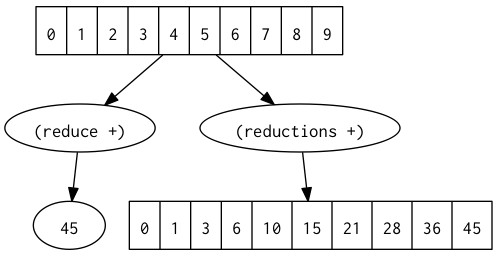

map

In mathematical terms mapping is the transformation of values through the application of a function. In Clojure the map function is one of the most often used functions. It takes a transformation function and applies it to each element in a given collection/sequence. E.g. The example below takes the function inc and a seq of numbers. It then applies inc to each number individually and returns a new sequence of the results:

(map inc [1 2 3 4 5])

; (2 3 4 5 6)

The transformation function given to map can be anything and its also one of the situations where anonymous functions are often used. E.g. Here we produce a seq of square numbers:

(map (fn [x] (* x x)) [1 2 3 4 5])

; (1 4 9 16 25)As an aside, since anonymous functions are often very short, they can also be defined more concisely (though become less legible). The following is equivalent to the above expression:

(map #(* % %) [1 2 3 4 5])

; (1 4 9 16 25)Here we use the reader macro #(..) to define an anon fn and the symbol % to refer to the first (in this case only) argument. If such a function takes more than a single arg, then we can use %2, %3 etc. to refer to these...

(#(* % %2) 10 2) ; call anon fn with args: 10, 2

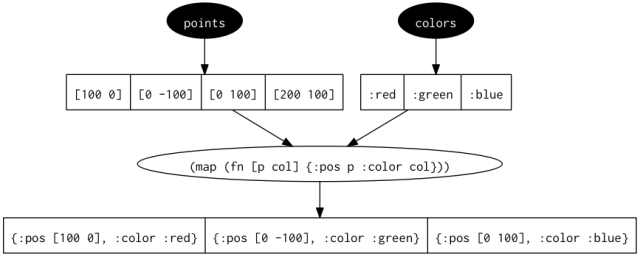

; 20map can also be applied to several collections at once. In this case the transformation function needs to accept as many parameters as there are collections. Let's use map to build a seq of hashmaps from two vectors of point coordinates and colors. Each time our transformation fn is given a single point (a vector) and a color keyword. The fn simply combines these values into a single map with keys :pos and :color:

(map

(fn [p c] {:pos p :color c}) ; transformation fn

[[100 0] [0 -100] [0 100] [200 100]] ; points

[:red :green :blue]) ; colors

; ({:pos [100 0], :color :red}

; {:pos [0 -100], :color :green}

; {:pos [0 100], :color :blue})

Important: You might have noticed that our vector of points has one more element than there're colors. In that case,

mapwill stop as soon as one of the input collections is exhausted / has no further values. In this case we only have 3 colors, so the last (4th) point is ignored.

Laziness and lazy seqs

One thing not immediately obvious when experimenting with map in the REPL, is that the seq returned by map is a so called lazy-seq, that is, the transformation function is actually not applied to our original values until their results are needed. In other words, map is more of a recipe for a computation, but the computation does not ever happen if we don't attempt to use its results.

To illustrate this better, let's again simulate a slow transformation function which takes 1 second per value. With 5 values in the original collection, our entire processing should take approx. 5 seconds:

(def results

(map

(fn [x]

(Thread/sleep 1000)

(* x 10))

[1 2 3 4 5]))When this code executes, we can see the REPL immediately returned a result, the new Var user/results. It did not take 5 seconds, because at this stage we haven't yet attempted to do anything with that new Var - and hence no mapping did take place thus far. It's plain lazy!.

Now trying to display the contents of results however will force the computation and therefore will take 5 seconds until we can see the mapped values:

results ; takes ~5secs, world's slowest multiply

; (20 30 40 50 60)reduce

reduce is Clojure's natural way of expressing an accumulation over a sequence of values. Like map it takes a function, an optional initial result and a sequence whose elements will be passed to the transformation function individually, for example:

(reduce + 0 [1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10])

; 55In this case reduce uses the function + to combine all values of our seq into the accumulated result one by one. The transformation function must always take 2 arguments: the current result (reduced value) and the next item to be processed. If no initial result is given, the first iteration will consume the first 2 items from the sequence.

In our case this happens:

(+ 0 1) ; 0 is the initial result, returns 1

(+ 1 2) ; 1 is current result, returns 3

(+ 3 3) ; returns 6

; and so on until the seq is exhausted...Clojure also provides an alternative to reduce, called reductions. Instead of the just final reduction it returns a seq of all intermediate results (here we also use range to create a seq of numbers from 0-9):

(reduce + (range 10))

; 45

(reductions + (range 10))

; (0 1 3 6 10 15 21 28 36 45)

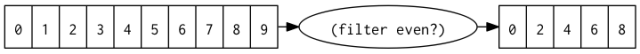

filter

filter takes a function and a seq, then applies the function to each element and returns a lazyseq of only the elements the function returned a "truthy" value for. These kind of functions are also called "predicates".

Clojure has a number of predicate functions which rely on truthiness and they can be easily recognized by their general naming convention, a function name suffixed with ?. E.g. even? can be used to filter out all even numbers from the seq of numbers 0-9:

(filter even? (range 10))

; (0 2 4 6 8)

Since the function needn't strictly return true or false, we can also use a set as predicate to filter out only values which are present in the set:

(filter #{1 2 4 8 16 32} (range 10))

; (1 2 4 8)Again we're using data as code, since vectors, maps & sets all can be used as functions and return nil if a value isn't present, therefore fulfilling the general contract of a predicate function...

take / drop

Sometimes we are only interested in a chunk of values from a larger collection. We can use take to retrieve the first n elements from a collection as a lazy sequence:

(take 3 '(a b c d e f))

; (a b c)In contrast, we can use drop to ignore the first n elements and give us a lazy sequence of all remaining elements:

(drop 3 '(a b c d e f))

; (d e f)Clojure has a few other variations on that theme, most notably take-last, drop-last, butlast, take-nth, take-while and drop-while. The latter two also take a predicate function and terminate as soon as the predicate returns a "falsy" result:

(take-while #(< % 5) (range 10))

; (0 1 2 3 4)concat & mapcat

concat splices any number of seqs together into a single new lazy seq. The new `rotate-left` function shows how we can use `concat` with `take`/`drop` to rotate elements in a sequence:

(concat [1 2 3] '(a b c) {:a "aa" :b "bb})

; (1 2 3 a b c [:a "aa"] [:b "bb"])

(defn rotate-left [n coll] (concat (drop n coll) (take n coll)))

; #'users/rotate-left

(rotate-left 3 '(a b c d e f g h i))

; (d e f g h i a b c)mapcat is a combination of map & concat. Like map it accepts a transformation function and a (number of) seqs. The mapping function needs to produce a collection for each step which are then concatenated using concat:

; another social graph structure as from above (only w/ more people)...

(def g2

#{#{:ricardo :toxi}

#{:filip :edu}

#{:filip :toxi}

#{:filip :ricardo}

#{:filip :marija}

#{:toxi :marija}

#{:marija :edu}

#{:edu :toxi}})

; step 1: produce a seq of all relations

(map seq g2)

; ((:marija :filip) (:toxi :marija) (:edu :filip) (:ricardo :filip)

; (:toxi :edu) (:toxi :ricardo) (:marija :edu) (:toxi :filip))

; step 2: combine rels into single seq

(mapcat seq g2) ; option #1: `seq` as transform fn

(mapcat identity g2) ; option #2: `identity` as transform (same result)

; (:marija :filip :toxi :marija :edu :filip :ricardo :filip :toxi :edu :toxi :ricardo :marija :edu :toxi :filip)

; step 3: form a set of unique nodes in the graph

(set (mapcat identity g2))

; #{:toxi :marija :edu :ricardo :filip}

; step 4: build map of node valence/connectivity

(frequencies (mapcat identity g2))

; {:marija 3, :filip 4, :toxi 4, :edu 3, :ricardo 2}There're two functions we haven't dealt with so far:

identitysimply returns the value given as argument.frequenciesconsumes a seq and returns a map with the seq's unique values as keys and their number of occurrences as values, basically a histogram.

take & drop are also important with respect to one more (optional) property of lazy sequences we haven't mentioned so far:

Infinite sequences

The concept of infinite data in a non-lazy (i.e. eager) context is obviously unachievable on a machine with finite memory. Laziness, however does enable potential infinity, both in terms of generating and/or consuming. In fact, there're many Clojure functions which exactly do that and without the proper precautions (i.e. combined with take, drop and friends), they would bring a machine to its knees. So be careful!

We already have used one of these potentially infinite sequence generators above: range when called without an argument produces a lazyseq of monotonically increasing numbers: (0 1 2 3 4 ...) (Since the REPL always tries to print out the result, do not ever call one of these without guards in the REPL!)

Other useful infinite lazyseq generators are:

cycle delivers a lazyseq by repeating a given seq ad infinitum:

(take 5 (cycle [1 2 3]))

; (1 2 3 1 2)

(take 10 (take-nth 3 (cycle (range 10))))

; (0 3 6 9 2 5 8 1 4 7)repeat produces a lazyseq of a given value:

(take 5 (repeat 42))

; (42 42 42 42 42)

(repeat 5 42)

; (42 42 42 42 42)repeatedly produces a lazyseq of the results of calling a function (without arguments) repeatedly:

(take 5 (repeatedly rand))

; (0.07610618695828963 0.3862058886976354 0.9787365745813027 0.6499681207528709 0.5344143491834465)iterate takes a function and a start argument and produces a lazyseq of values returned by applying the function to the previous result: so (f (f (f x)))... Here to generate powers of 2:

(take 5 (iterate #(* 2 %) 1))

; (1 2 4 8 16)

(take 5 (drop 10 (iterate #(* 2 %) 1)))

; (1024 2048 4096 8192 16384)Since infinite lazyseqs are values just like any other (but at the same time can't be exhausted) it sometimes it's helpful to think about them as high level recipes for changing program states or triggers of computations. Combined with the various sequence processing functions they provide a truly alternative approach to solving common programming problems.

Sequence (re)combinators

Here're some more core functions related to combining collections in different ways:

interleave recombines two sequences in an alternating manner (also lazy):

(interleave [:clojure :lisp :scheme] [2007 1958 1970])

; (:clojure 2007 :lisp 1958 :scheme 1970)interpose inserts a separator between each element of the original seq:

(interpose "," #{"cyan" "black" "yellow" "magenta"})

; ("cyan" "," "magenta" "," "yellow" "," "black")zipmap combines two collections into a single hashmap, where the 1st collection is used for keys and the second as values. Let's have some Roman Numerals:

; first the individual pieces:

; powers of 10

(take 10 (iterate #(* 10 %) 1))

; (1 10 100 1000 10000 100000 1000000 10000000 100000000 1000000000)

; apply powers to 1 & 5

(take 5 (map (fn [x] [x (* x 5)]) (iterate #(* 10 %) 1))) ; using `map`

; ([1 5] [10 50] [100 500] [1000 5000] [10000 50000])

(take 5 (mapcat (fn [x] [x (* x 5)]) (iterate #(* 10 %) 1))) ; using `mapcat`

; (1 5 10 50 100)

; altogether now...

(zipmap

[:I :V :X :L :C :D :M] ; keys

(mapcat (fn [x] [x (* x 5)]) (iterate #(* 10 %) 1))) ; values

; {:M 1000, :D 500, :C 100, :L 50, :X 10, :V 5, :I 1}for

Since we've just discussed sequence generators, we also must briefly mention for. Unlike for loops in other languages, Clojure's for is a so called List comprehension, just another generator of lazyseqs, though one on crack if we may say so... for combines the behavior of map with lexical binding as we know from let and conditional processing. It returns its results as lazyseq. Here we iterate over the seq returned by (range 4) and bind i to each value successively, then execute for's body to tell us if that current value of i is even:

(for [i (range 4)] {:i i :even (even? i)})

; ({:i 0, :even true} {:i 1, :even false} {:i 2, :even true} {:i 3, :even false})

(into {} (for [i (range 4)] [i (even? i)]))

; {0 true, 1 false, 2 true, 3 false}for can also be used to created nested seqs. This happens automatically when more than one symbol is bound, e.g. here we create positions in a 4x2 grid (the first symbol defines the outer loop, the next one(s) inner loops:

(for [y (range 2) ; outer loop

x (range 4)] ; inner loop

[x y]) ; result per iteration

; ([0 0] [1 0] [2 0] [3 0] [0 1] [1 1] [2 1] [3 1])The symbol binding part can be further customized with additional bindings to pre-compute values used in the body of for and/or we can specify a predicate to skip an iteration (therefore also achieving filtering a la filter) or cancel iteration (using :while). The next example creates points only along the border of a 4x4 grid (center points are skipped):

(for [y (range 4)

x (range 4)

:let [border? (or (= 0 x) (= 3 x) (= 0 y) (= 3 y))]

:when border?] ; skip iteration when border? is false

[x y])

; ([0 0] [1 0] [2 0] [3 0] ; manually formatted to better visualize result...

; [0 1] [3 1]

; [0 2] [3 2]

; [0 3] [1 3] [2 3] [3 3])every? / some

Sometimes we need to check if the values of a collection match certain criteria, e.g. to enforce a restriction. The every? function takes a validation function (predicate) and applies it to all elements of a collection. It only returns true, if the predicate returns a truthy value for all of them. Here we check if all elements in a seq have a :name key (remember, keywords can be used as functions!)

(every? :name [{:name "nardove"} {:name "toxi"} {:age 88}])