Since ECAL’s R&D department opened in the year 2000, the Swiss art and design school conducted more than thirty research projects into everything from data materiality to augmented photography to artificial intelligence. In November 2019, CAN joined the biannual ECAL Research Day to find out how methodologies borrowed from science and engineering can strengthen creative practice—and drive the conversation.

“Art and design schools are perhaps the single most important degree in the future,” said American designer and computer scientist Skylar Tibbits in a 2017 interview. “They can teach you to imagine and create, to conceptualize, visualize and physicalize in ways that almost no other degree can.” An MIT graduate who went on to found MIT’s Self-Assembly Lab, a research unit focused on programmable material technologies he now co-directs, Tibbits knows what art schools are capable of — and why many of them fall short. “All too often, the emerging projects, while thoughtful and beautifully crafted, don’t work under the hood — there’s too much smoke and mirrors.” The result, he said, are great ideas that are barely feasible to implement and unlikely to have any impact in the real world. This is where he suggests art and design can learn from science and engineering. Here we find rigor in research, development, and knowledge production that, woven into art and design education, can foster a mindset that not only creates new ideas and things of beauty but work that is “conceptually and technically robust.”

Tibbits’ antidisciplinary sentiments, of course, have precedents. In 1960, a time when the computer, cybernetics, and information theory first entered the artists’ vocabulary, German philosopher Max Bense wrote that “in a technological society, there is, at least in principle, no fundamental difference between research and artistic productivity.” This proposed confluence of attributes, practices and methodologies — designers doing research, science informing art — has been subject to discussion and attempts of formalisation ever since. In 2016, Tibbits’ MIT colleague Neri Oxman, head of the Mediated Matter group, famously wrote that “knowledge can no longer be ascribed to, or produced within, disciplinary boundaries, but is entirely entangled.” The now seminal essay included the ‘Krebs Cycle of Creativity,’ a “cartography of the interrelation of domains” — art, design, engineering, science — that suggests that “a single individual or project can reside in multiple dominions.” If true, art and design schools must adapt.

“In a technological society, there is, at least in principle, no fundamental difference between research and artistic productivity.”

→ Max Bense, aesthetica IV, Programmierung des Schönen (1960)

Tibbits’ statements are taken from one of two “Conversations on Design Research” included in Making Sense: 10 Years of Research in Art & Design at ECAL. Published in 2017, the 238-page volume recounts how the renowned art and design school in Western Switzerland infused its educational activities with a sufficiently ‘entangled’ research program, strengthening not only the ‘robustness’ but the relevance of the emerging work.

A Brief History of Research at ECAL

Regularly listed amongst the world’s top ten universities of art and design, ECAL (École cantonale d’art de Lausanne) needs little introduction: with nearly 100 related entries in the CAN archive the school remains one of the most reliable sources of truly forward-thinking work. This consistency is no accident. Based in Renens, an industrial neighbourhood at the edge of Lausanne, ECAL offers students — currently about 600 from 40 different countries — an exceptional learning environment: the 18,000 sqm campus, a former knitwear factory redesigned by Bernard Tschumi Architects, is outfitted with state-of-the-art technology, its own printing center and a 500 sqm exhibition space, L’elac gallery. It’s also home to the EPFL+ECAL Lab, a two-floor design research and innovation centre run together with the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (Ecole Polytechnique Federal de Lausanne). It is here where many of ECAL’s functional prototypes are being built and where international partnerships with industry and institutions plug into.

Driving experimentation across departments and courses is, of course, ECAL’s own R&D unit. Set up in September 2000 to comply with federal mandates — with the founding of Swiss HES, a group of 28 universities in Western Switzerland, art and design schools were tasked with applied research and development — the new division was off to a slow start. “These first years were mainly devoted to ‘learning by doing’,” recalls Luc Bergeron, who led the department between 2000 and 2016, in Making Sense. “Then, little by little, with experience gained and a growing interest in research, the number of projects increased and became considerably more diverse in nature.” Adopting forms of theoretical research, applied research, and research-creation, the department decided to support “the widest possible range of initiatives, ranging from the most traditional to the most unusual,” notes Bergeron. “Our objectives are deepening knowledge in the disciplines we teach, opening our teaching up to new issues and methodologies, and developing partnerships and exchanges with academic, institutional, and economic circles.”

“Our objectives are deepening knowledge in the disciplines we teach, opening our teaching up to new issues and methodologies, and developing partnerships and exchanges with academic, institutional, and economic circles.”

→ Luc Bergeron, ECAL head of R&D (2000-16)

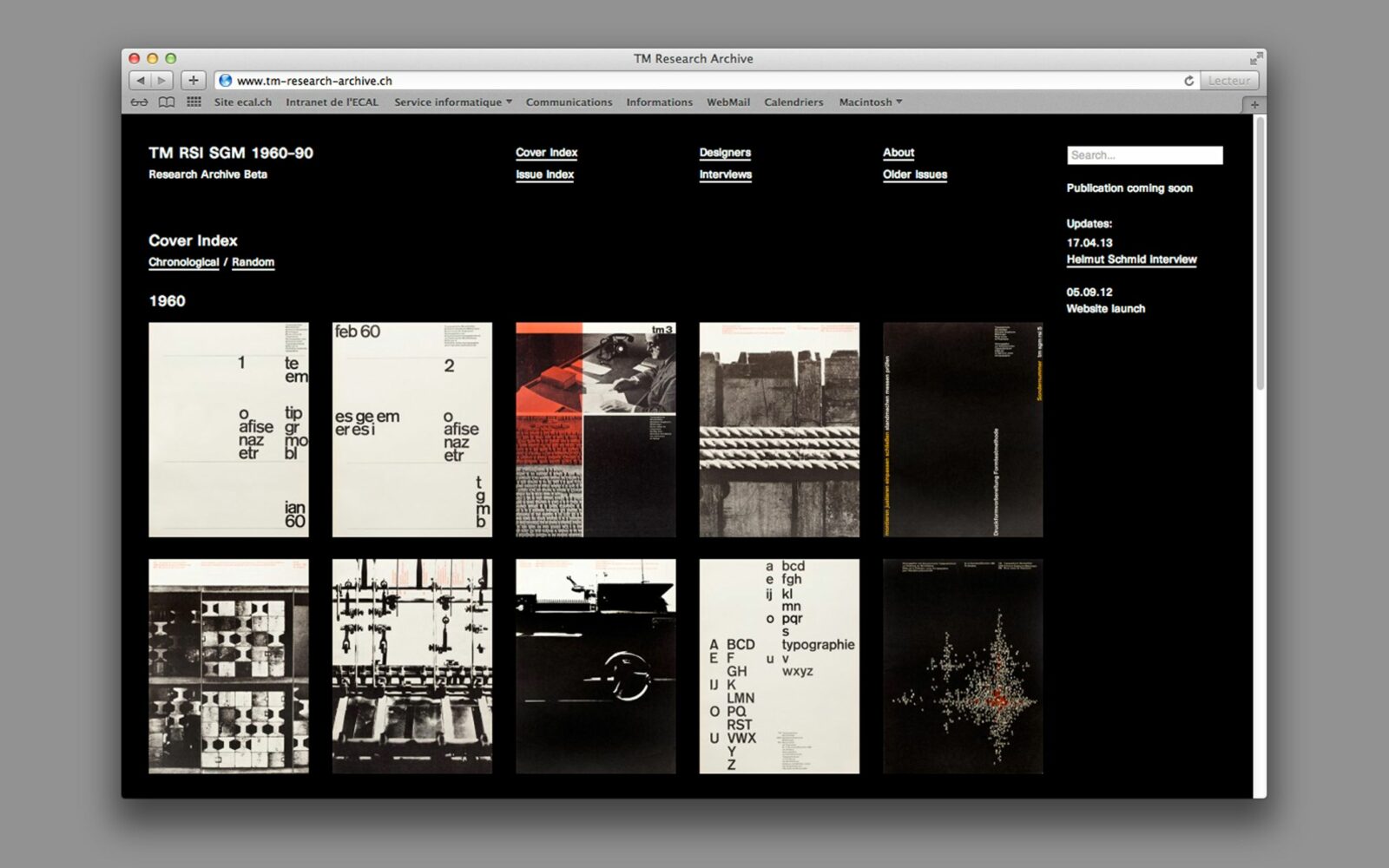

Since 2006, when the department came fully into its own, more than thirty research projects have been completed, investigating everything from forgotten chapters of Swiss typographic history, to design tools incorporating generative principles, to the rise of augmented photography. “Research is carried out into all the disciplinary remits of the school’s courses,” explains Davide Fornari, ECAL’s current head of R&D. The difference between academic research and research in art and design, he explains, are modes of inquiry and output. Whereas scientists, for example, maintain utmost neutrality towards a studied subject, artists and designers approach it through personal and often critical practice. And where the former produce knowledge primarily via (often inaccessible) papers and patents, the latter express findings in a variety of engaging formats: books and films, objects and systems, exhibitions, and performances. ‘Theater, Garden, Bestiary: A Materialist History of Exhibitions’ (2015-18), for example, critically examined exhibition design throughout the ages and, in addition to a lecture series, put out an eponymous book (published by Sternberg Press no less). ‘Smartphone Peripheral Companions’ (2018-20) yielded ten objects — semi-functional prototypes — that ‘break’ our smartphone behavioral patterns. Additionally, the project produced an exhibition, DIY toolkits for reproduction, and an ongoing survey on people’s smartphone use.

Naturally, technology and its impacts on society are at the heart of many ECAL research projects. “Design and the arts are a crucial way of applying technology and making it socially accepted,” says Fornari — design as a way of expressing technology and art as a way of questioning it. That’s why ECAL’s research domain sits at the “nexus of technology, art, and design,” he explains. To Fornari, technology is the barometer of societal change and, increasingly, our planetary challenges. “The research projects aim to expose students to these issues at an early stage in their careers, in order to provide long-term benefits to society.”

Projects driving conversation: The ECAL Research Day 2019

Calibrating the school’s research towards providing long-term benefits to society requires openness and opportunities for public conversation. One such opportunity is the ECAL Research Day. First held in 2015, the (more or less) biannual symposium is a public forum where the school demonstrates not only how its research intersects with industry and other institutions, but how results can be opened up in a discussion. The format: ECAL educators unpack research process, outcomes, and wider implications of recent projects with invited guests.

For its latest edition, held on November 8th, 2019, David Fornari brought together select faculty members (Patrick Keller, Kai Bernau, Nicolas Henchoz, Thilo Alex Brunner, Pauline Saglio), industry experts (Christian Kaegi, Fabrice Aeberhard), cultural producers (Natalie D. Kane, Hughes Binet, Ala Tannier) and creative practitioners (Bianca Berning, Christian Mio Loclair, Mario de Vega) to contextualise research projects from a multitude of angles. Covering everything from data practice and AI, to typography and design, to sustainability and activism, the talks and conversations touched on many key issues today’s artists and designers are grappling with: what are the true costs of the products, tools, and services we use? How does technology warp our sense of self? And how can we create responsibly in the face of an unfolding planetary crisis?

CAN was invited to take notes that day (some of which we shared live on Instagram). From our front-row seat in ECAL’s IKEA auditorium, we watched speakers and faculty cover tremendous ground. And while not nearly a complete account — we encourage readers to watch the talks linked at the end of this post! — the following exchanges have stuck with us.

Of data ghosts and dust bunnies: Natalie D. Kane and Patrick Keller on “Inhabiting the Cloud”

In 2012, a survey conducted by Wakefield Research for U.S. software company Citrix revealed that 51 percent of Americans think that bad weather directly affects cloud computing. A whopping 95 percent claimed they never use the cloud while happily admitting to online banking, social networking, and storing photos and music online. At the time, the press responded with a mix of disbelief and schadenfreude (British technology tabloid The Inquirer: “Worst. Poll Result. Zephyr” and “You cannot be cirrus”). But if the same survey were held today — U.S. internet traffic has since more than doubled — would the results be that much different?

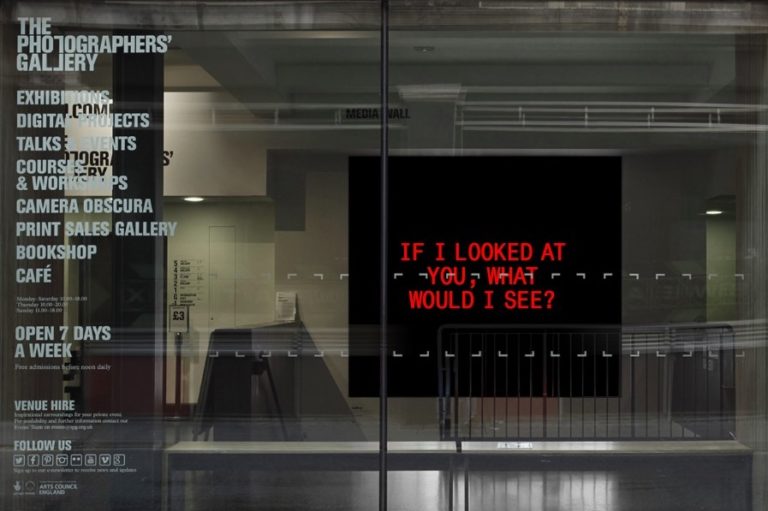

“When asked where the cloud is, most people still point to the sky, not the nearest data center,” said Natalie D. Kane to ECAL’s Patrick Keller during the opening conversation. As the V&A Museum’s digital design curator and one half of Haunted Machines, a research project she runs together with designer Tobias Revell, Kane is particularly interested in the narratives we construct around technology; technology whose inner workings are either deliberately obfuscated or impossible to unpack for most. As such, “the cloud has become a cultural phenomenon as much as it is a technology,” said Kane.

“When asked where the cloud is, most people still point to the sky, not the nearest data center. The cloud has become a cultural phenomenon as much as it is a technology.”

→ Natalie D. Kane, V&A Museum / Haunted Machines

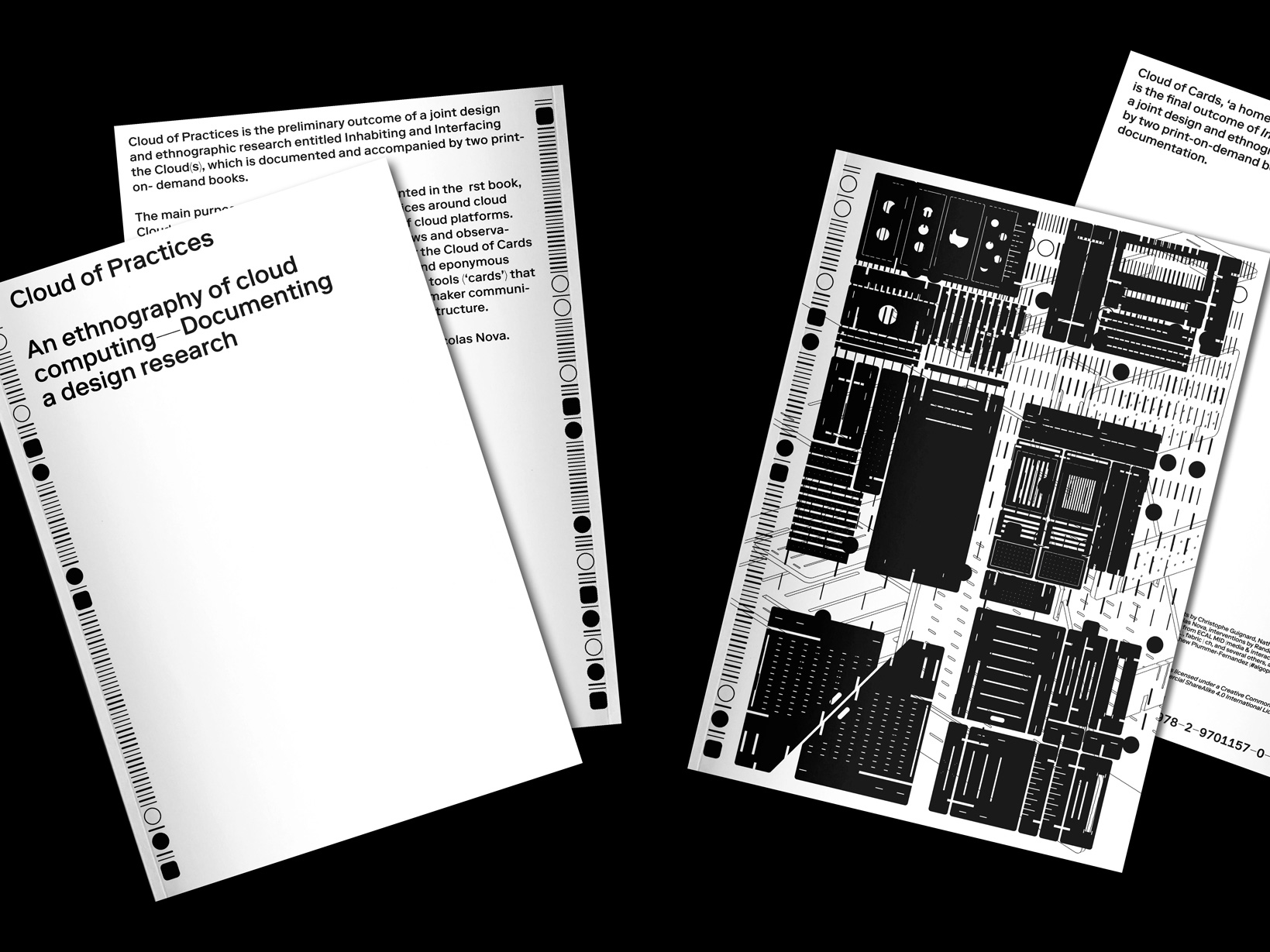

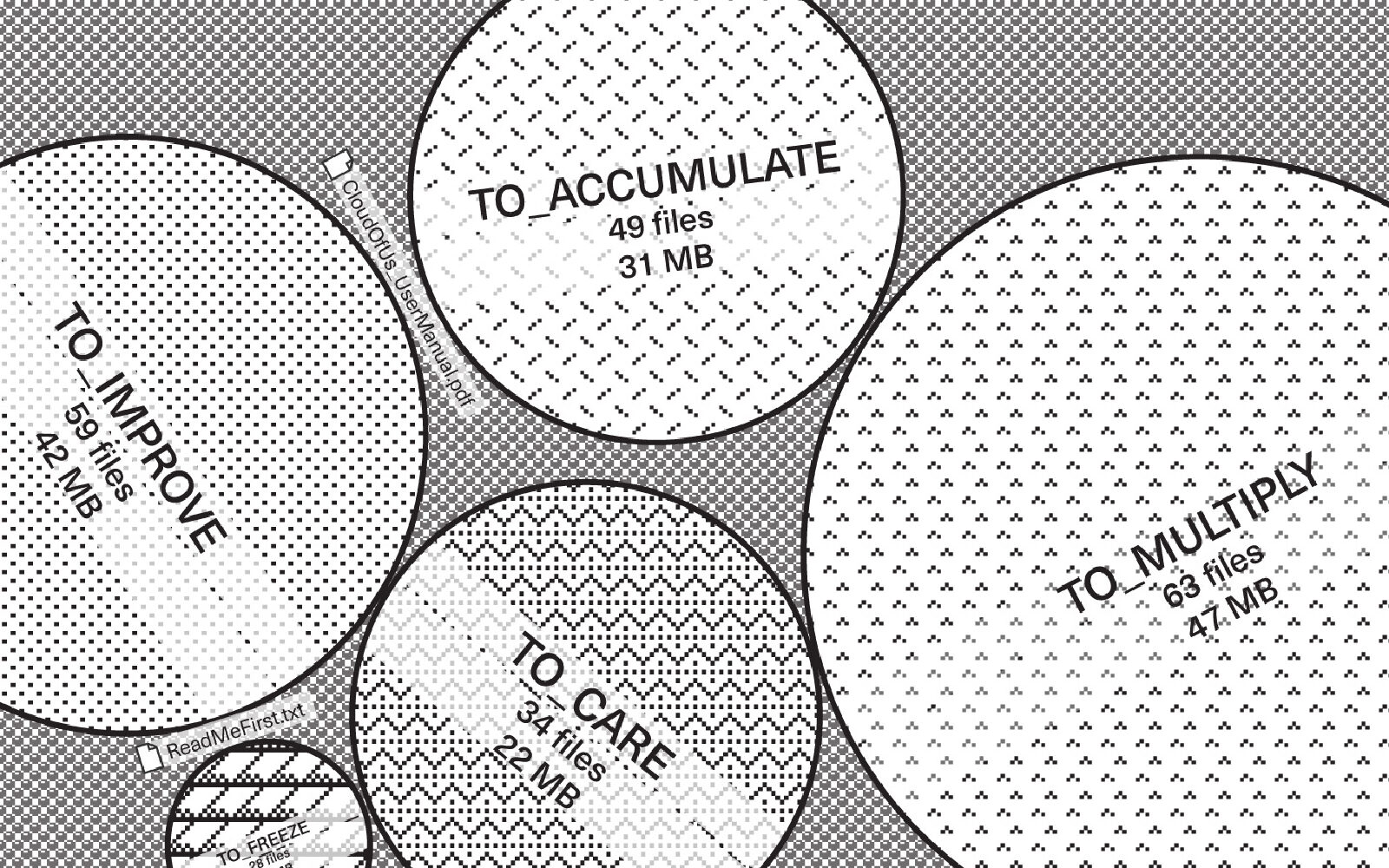

Keller, professor at ECAL’s media & interaction design department, was uniquely qualified to lead this conversation. In 2014, two years after the Citrix survey and decades after ARPANET researchers first coined the term, he launched a 4-year investigation into what remains one of computing’s most misleading metaphors. ‘Inhabiting and Interfacing the Cloud(s)’ (I&IC) was a joint design and ethnographic research project with HEAD Geneve’s Nicolas Nova that explored cloud counter-narratives together with students and key practitioners such as Random International, Matthew Plummer-Fernandez, and the late Sascha Pohflepp. At the time, Keller described the data center as the paradoxical new main vector of our personal relationship to information. Sold “on a grand scale” as “the very idea of dematerialization,” the cloud is, in fact, “physical, proprietary, precisely located, and heavily centralized.” Today, in the age of streaming services, the disconnect between what the cloud is and how most people experience it has further widened, suggested Keller. Oblivious to the far-away always-on data fortresses where it is stored, we consume media via slick interfaces and innocuous iconography — “the little cloud in the corner of your screen” — that imply weightlessness and zero friction. “It’s how corporations want us to think of the cloud,“ said Kane. “It’s how they sell the idea of having ‘the better cloud’. And the more mundane the product the more fantastical the imagery becomes.”

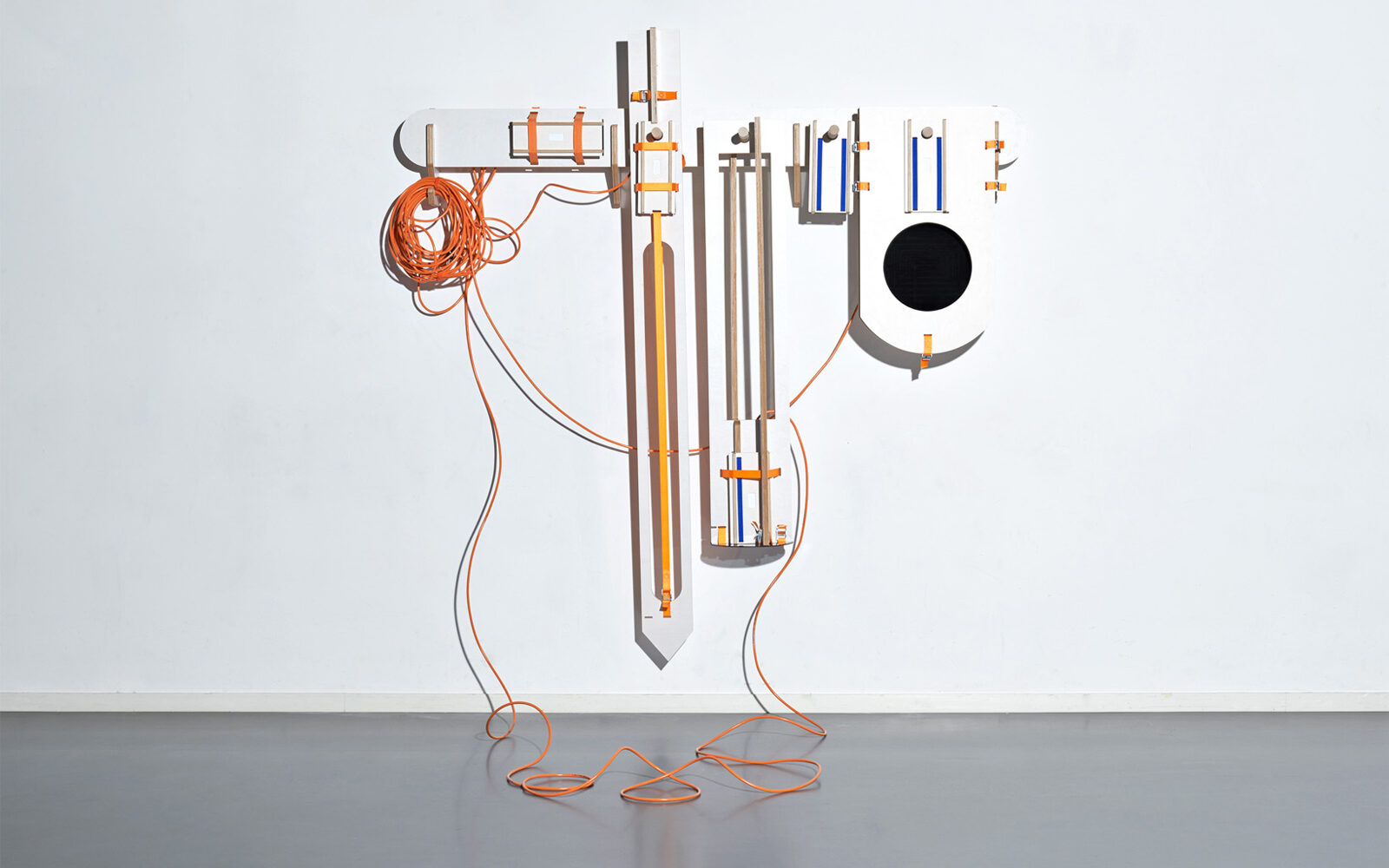

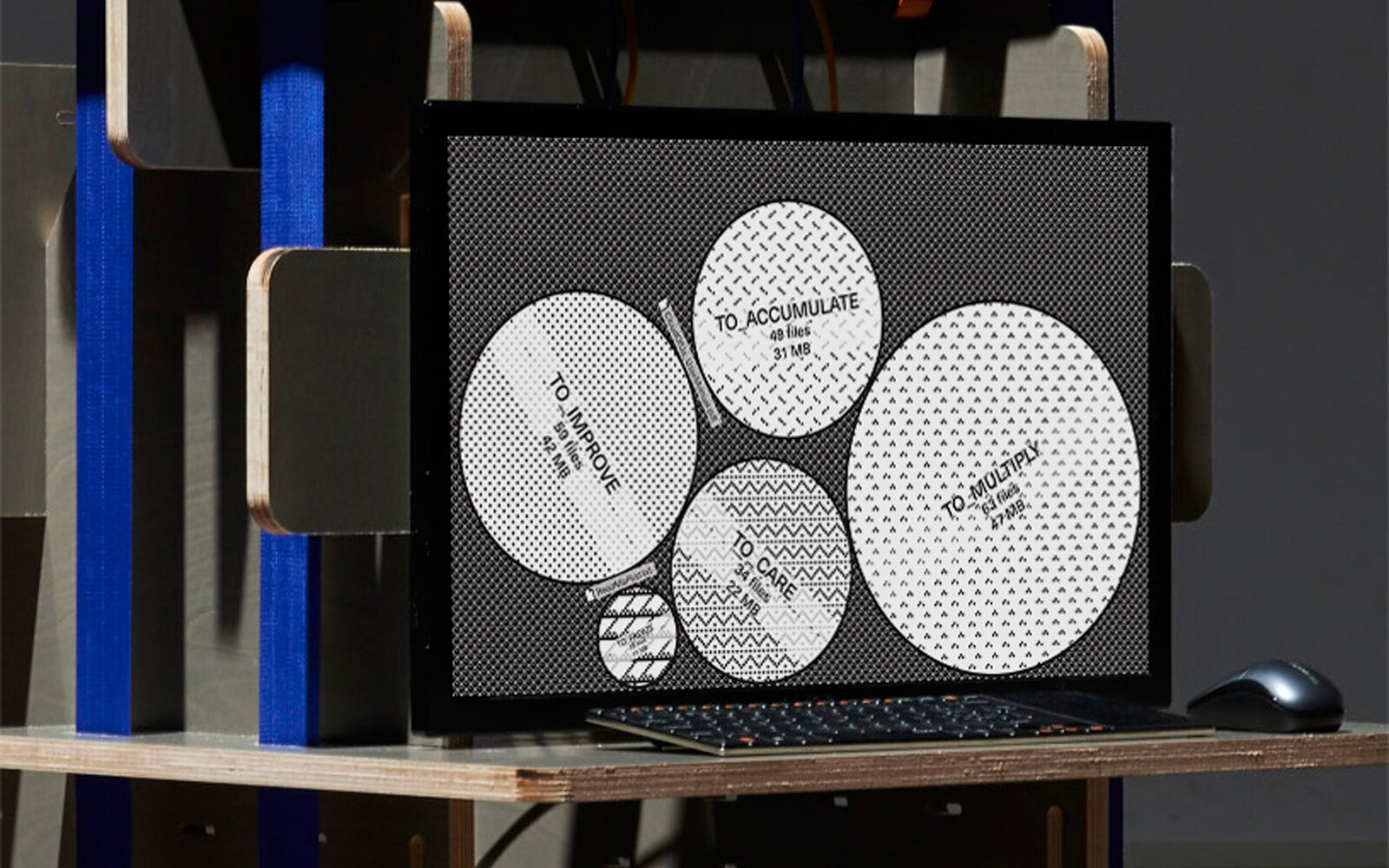

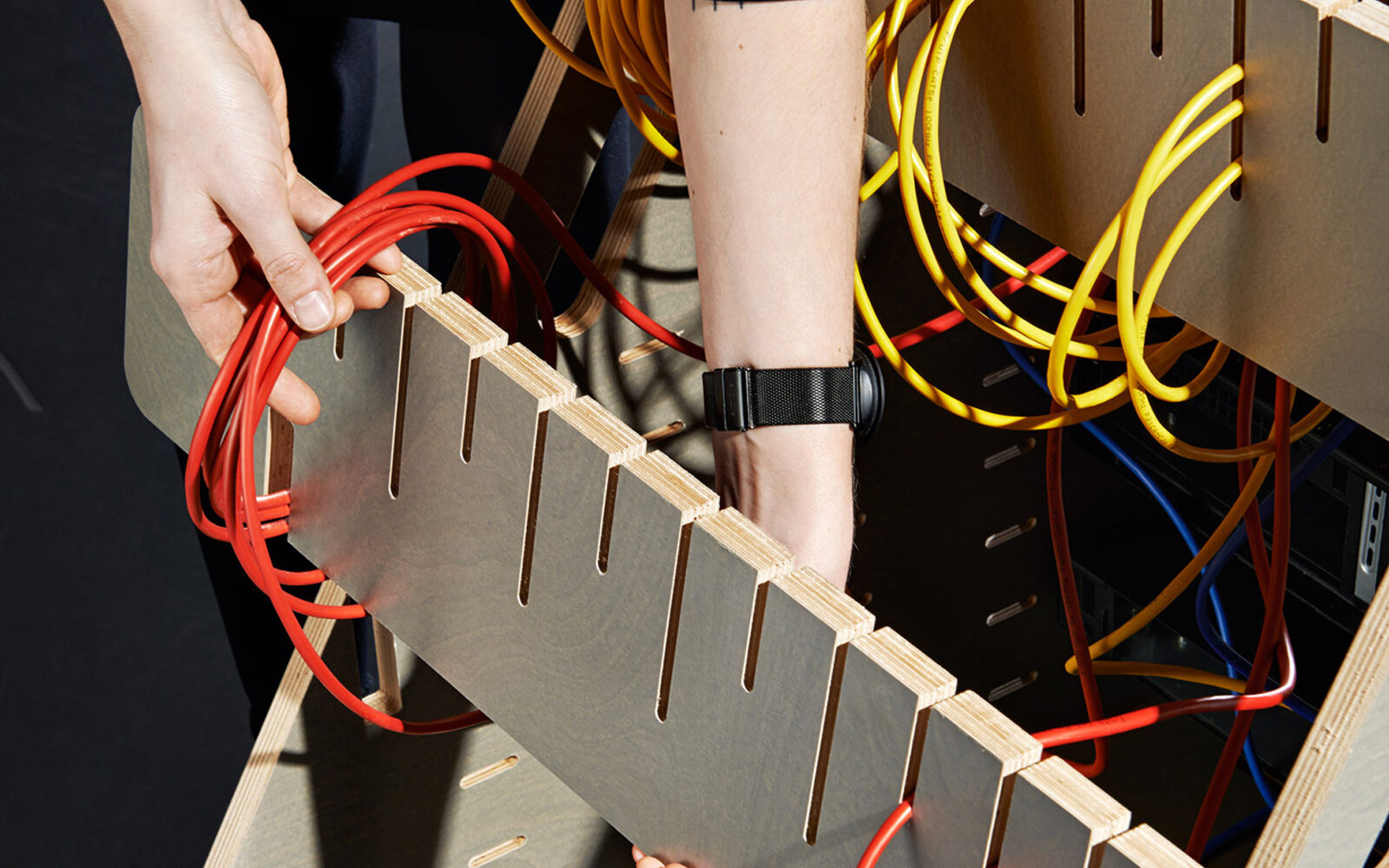

That’s why it’s important to reintroduce friction that reminds us of the cloud’s materiality, Keller and Kane agreed. I&IC’s main output, for example, was Cloud of Cards, a home cloud kit to “re-appropriate your data self.” Comprised of four digital and physical artifacts, the kit invites anyone to DIY their own small-scale data center. “It sought to make the cloud truly ‘personal’, in order to give access to tools to design and maker communities,” stated Keller. To Kane, Cloud of Cards is exemplary because it unpacks complexity through analogies of personal scale: the “19” Living Rack”, an open-source variation of the standardized 19” computer server rack that doubles as modular office furniture; “5 Connected Objects” which materialise the ‘ghostly’ presence of cloud user data and our fear of file loss. “I like the cup that deletes files when dropped,” said Kane of the project’s clever physical representation of everyday data mishaps. ”It’s important for designers to think through the breaking points of how data is being handled and collected.”

Kane also reminded us that the data that accumulates in hidden infrastructures can be weaponised to affect the body. “Cathy O’Neil calls them ‘Weapons of Math Destruction’ for a reason,” said Kane. In her eponymous book, the former Wall Street quant turned data scientist unpacks mathematical models or algorithms that claim to quantify important traits—teacher quality, recidivism risk, creditworthiness—but often reinforce inequality. In 2016, for example, Pro Publica reported the case of 18-year-old Brisha Borden and 41-year-old Vernon Prater. The former is schoolgirl wrongly accused of petty theft, the latter a seasoned criminal who was caught shoplifting. “Yet something odd happened when Borden and Prater were booked into jail,” states the article. ”A computer program spat out a score predicting the likelihood of each committing a future crime. Borden — who is black — was rated a high risk. Prater — who is white — was rated a low risk.” These risk assessment scores were based on a (racist) dataset by the Chicago Police; similar ones are increasingly common in courtrooms across the United States.

On the other end of the spectrum sit startups like eterni.me. “Become virtually immortal,” states the website — by sharing your social media activity, your emails and intimate details with us so that your digital avatar, trained with your personal data, can speak to your descendants in the future. “I’ve been following eternity.me for about six years and all this time they’ve been in beta,” said Kane. “They’re obviously building their dataset, but nobody knows what exactly they do with the data or when the service will go live.” That didn’t stop 46,318 people from signing up.

“Data and analytical models can also be used to affect the body. Cathy O’Neil calls them ‘Weapons of Math Destruction’ for a reason.”

→ Natalie D. Kane, V&A Museum / Haunted Machines

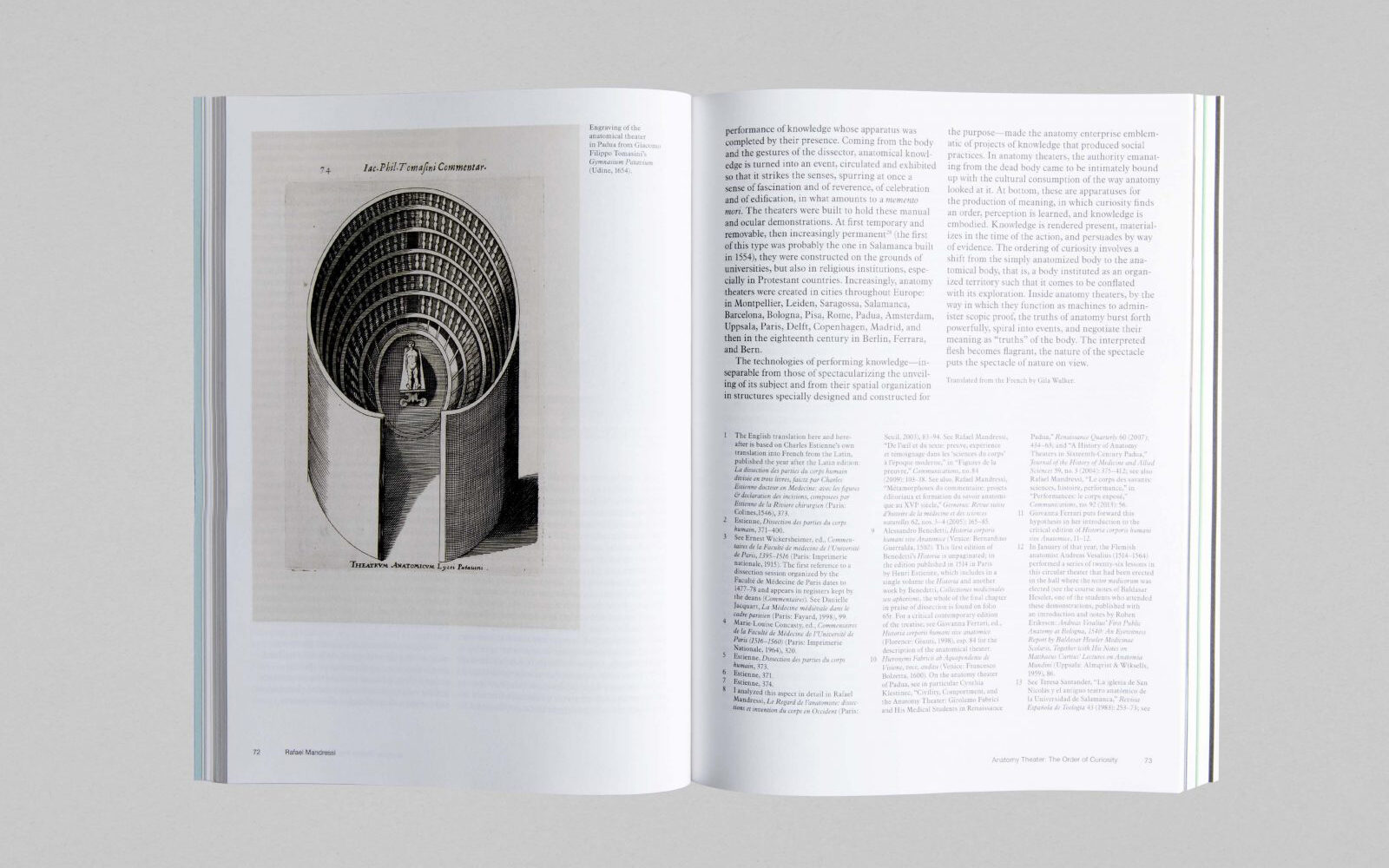

There are, of course, already many different versions of ourselves all over the Internet. And for the most part, these ‘doppelgangers’ — MIT’s Sun-ha Hong calls them “trace bodies” — are being generated without our knowledge or informed consent. In 2018, the V&A Museum showed Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler’s Anatomy of an AI System (2017) as part of the show ‘Artificially Intelligent’. The project breaks down the Amazon Echo as an anatomical map of human labor, data and planetary resources. The device itself: only a small node within a vast matrix of capacities invisible to the end-user. “Echo sales are a net loss for Amazon, but it’s a powerful conduit to get to your data,” said Kane.

Digital data can also materialise in unsuspected ways. Alan Warburton’s Dust Bunny (2015) — cited as one of Kane’s favourites — is made from the dust collected from the inside of ten 3D animation workstations at British visual effects studio Mainframe. The sculpture represents the Standford Bunny, a now iconic 3D test object introduced in early computer graphics experiments at Stanford University. The volume of dust that makes up the fist-sized object represents an estimated 35,000 hours, or 4 years, of constant rendering and processing. “I like this project not only because shows the material that can be generated from something we often see as immaterial, but because it speaks to the time and labour required for digital imagery — something we don’t often think about.”

Another Kane favourite is Ripple Counter (2012), one of seven Sublime Gadgets created by speculative designers James Auger and Jimmy Loizeau. Kane had included Ripple Counter in the ‘Myth, Magic, and Monsters’ exhibition at Utrecht’s Impakt Festival 2017, which Haunted Machines had been invited to curate that year. Shown alongside, for example, James Bridle’s Autonomous Trap (2017) and Addie Wagenknecht’s Internet of Things (2016), the esoteric floating tripod provoked questions around the innate knowledge that we — falsely — assume in technology and how increased machine complexity inspires mythology and magical thinking. “Ripple Counter attempts to count waves and is part of a series of machines that try to do fantastical if not impossible things,” explained Kane. “I really love this project because people would just walk around it and wonder how it worked and what it was doing. This question of ‘what is it doing?’ in regards to technology is central to our research.”

In the digital age, the answer to ‘what is it doing?’ increasingly appears to be a matter of belief, an observation that ‘Inhabiting and Interfacing the Cloud(s)’ (I&IC) addressed head-on. The briefs for “The Everlasting Shadow,” a one-week I&IC workshop lead by Random International’s Dev Joshi in 2015, were ‘haunted’ with mentions of “data ghosts” on “zombie servers,” Deleuze’s “corps sans organes” and references to spirituality and the Sublime (see here and here). “How many different versions of you are there in the cloud? If they could speak, what would they say?” asked Joshi and tasked students to interrogate the notion of self in an era of permanent personal data traces.

Is exorcism at all possible? In Presence, Persistence, Perception: Cloud Computing and the Body, the essay she contributed to the Cloud of Cards publication, Kane wrote that “resolutely, this is a conversation of power; who has the ability to enable and control the path of these phantoms, who stops them, who decides what shape they take.” Kane admits that there are no easy answers to these provocations, other than, perhaps, slowing down the pace of innovation; “enough for us to see where there are capacities for abuse, by imagining the future ghost stories and terrors, through rehearsal, foresight and analysis.” We might not be able to rid ourselves of what Kane calls “digitally-enabled poltergeists” completely, but “we may let our house become less vulnerable to haunting.”

Towards circularity: Christian Kaegi, Fabrice Aeberhard, and Thilo Alex Brunner on “The Aesthetics of Sustainability”

Whereas digital designers are just beginning to realise the material dimensions of their domain, product designers already have to think through issues of resource scarcity and waste. In 2015, the European Commission implemented the Circular Economy Action Plan to help companies transition to fully sustainable practices. Five years later, we’re no closer to circularity. Manufacturers that do attempt to ‘close the loop’ continue to struggle with material supplements and cost.

This is where Thilo Alex Brunner, ECAL’s head of product design (who also designs for running shoe brand ON), believes the school’s research can interface with industry. From September 2017 to July 2019, he led a research-by-practice project that investigated the production processes and (hidden) aesthetic potential of over 150 sustainable materials. Bringing together research assistants, guest lecturers, students, and companies, ‘The Aesthetics of Sustainability’ first researched and categorised available materials and then reached out to manufacturers for collaboration. “We ended up working with 16 companies, each paired with a student to explore new use cases for existing material.” The result, says Brunner, was a surprise success: rice husk powder was turned into pencils, industrial potato starch into egg packaging and a fibre made from eucalyptus and algae extracts became a waterproof sleeping bag.

To discuss the project’s outcome (which are due for publication in 2020), Brunner invited Swiss industry pioneers Christian Kaegi and Fabrice Aeberhard. Kaegi’s designer backpack brand QWSTION champions sustainable production practices with Bananatex®, a fully biodegradable textile engineered from banana fibres. Aeberhard, founder of VIU eyewear, ensures that each pair of VIU glasses is designed and handcrafted in Switzerland, using high quality, low-waste materials. To both, material research is inseparable from the design process.

“Most companies have no incentive to take care of the waste their products produce. In a circular economy, all externalities are priced into the product, effectively forcing companies to reduce waste.”

→ Christian Kaegi, QWSTION

Bananatex®, for example, was in development for four years. “Most bags are made from hard-to-recycle synthetic fibres,” explained Kaegi. “It’s cheap, waterproof, robust.” A true alternative has to have similar attributes—also aesthetically. The breakthrough came when Kaegi’s team discovered indigenous knowledge in Asia. A traditional Japanese yarn-from-paper technique was applied to sheets made from extra-strong banana fibres from the Philippines (where they have been used for rope-making for centuries). The resulting fully organic textile has all the qualities of its synthetic counterpart: it’s robust, straight and without the irregularities often found in natural fibres, explained Kaegi. “It almost has a technical feel to it.”

The ECAL research project went to similar lengths. “Our students had to develop a deep understanding of the materials and production processes their partnering company deployed,” explained Brunner. Fritz Jakob Gräber, for example, was embedded with isofloc AG, producers of a blown-in insulation material made out of recycled newspapers. After months of research and prototyping, he developed his own iteration — isofloc SOLID — that allowed him to cast the shapeless, unappealing material onto robust, aesthetic objects for everyday use. “The people from isofloc AG were impressed. They had no idea that you could create objects from their material, no less beautiful designed ones,” said Brunner. The product design Gräber eventually settled on was the Paper Paper Bin. “Today, the story a product tells is as important as the product itself,” quipped Brunner.

Kaegi and Aerberhard are well aware of the importance of a positive narrative. Both companies put a lot of effort into communicating their values. At Vienna Design Week 2019, for example, QWSTION presented an architectural installation that elegantly demonstrated the Banantex® lifecycle from raw fibre to finished bag. VIU leads by example in their stores: all materials are from sustainable sources (reclaimed wood for the counter, compressed recycled paper for the shelves). Store resource use recently went down from 3 tons to 1, and in 2020 the company will become fully carbon neutral. “It’s about transparency — and making people understand what they are paying for,” said Aerberhard.

Value-driven narratives like these are particularly important in a linear economy where, for example, 10$ t-shirts reinforce skewed customer expectations. The true costs, of course, are shouldered by society. “Most companies have no incentive to take care of the waste their products produce,” explained Kaegi. “In a circular economy, all externalities are priced into the product, effectively forcing companies to reduce waste.” However, not every ethical company has the means to tell their story and too many unethical ones spend a fortune greenwashing their products. That’s why circular business practices ought to be mandated by law, exclaimed Kaegi. “We’re about five to ten years away from that, I think.” Until then, it’s up to the individual — designers in particular — to take a stand.

Also: future letterforms, machine narcissism, and revolution

The protocolled exchanges above demonstrate the scope and richness of the conversations that were had that day. And there were a lot more topics tackled: Bianca Berning, font engineer at London’s Dalton Maag type foundry, explained type as the bedrock of written communication and how the lack of type literacy amongst developers is harmful to the web (according to Berning, part of the solution is a switch to variable fonts). Hugues Vinet, IRCAM-Centre Pompidou’s director of innovation and research, presented a distributed approach to R&D: in a conversation with EPFL+ECAL Lab founder and director Nicolas Henchoz, he unpacked not only IRCAM’s own research activities and (legendary) facilities but the more than 40 residencies it helps foster as part of STARTS, a European initiative that promotes the inclusion of artists in commercial innovation projects. In the context of several ECAL research projects on AI spoke artist, designer and CAN-favourite Christian Mio Loclair. In his (riveting!) lecture, the founder of Berlin-based studio Waltz Binaire speculated on the impact of artificial intelligence on art and design by connecting his background as a professional street dancer to the work he does now: creating thoughtful installations like Narciss (2018) — covered on CAN here — that deploy machine learning to muse on humanness and the “humanized machine.”

Meditations on art in the age of machine intelligence can seem trivial when the Amazon is burning and human rights are under threat. That’s why Ala Tannir, the co-curator of the 22nd Milan Triennale (themed “Broken Nature”), reminded us of the importance of art as activism. In her talk, she showcased works that dealt directly with environmental issues such as climate change, soil degradation, and plastic pollution. She also provided a window into the current turmoil in Lebanon (her country of origin), and how the people there use design and technology to bring about a revolution. Finally, the organisers knew how to match the cerebral part of the program with a more physical counterpart: Mario de Vega, an experimental sound artist from Mexico who participated in the 2018 ECAL research project ‘Vision Create New Sound’, closed the day with a tantalising performance.

What’s the takeaway? For us, the Research Day was a testament to the contributions artists and designers make to society and how research methodologies can increase their value. It also reminded us of how much of that value is tied to dialogue and collaboration, across disciplinary as well as institutional boundaries. To the involved students, educators, and partners, ECAL’s more than 30 completed research projects have already shown their value. Opening them up in discursive public settings is what makes them shine.

To learn more about recent ECAL research projects we recommend Technology and Research in Art and Design at ECAL. The sequel to 2015’s Making Sense was published in conjunction with the ECAL Research Day 2019 and, in addition to extensive project documentation, includes long-form interviews with musician Marianthi Papalexandri-Alexandri and type designer Kai Bernau.

ECAL | ECAL R&D | ECAL Research Day 2019

[two_columns_one] [/two_columns_one] [two_columns_one_last] [/two_columns_one_last] [two_columns_one] [/two_columns_one] [two_columns_one_last] [/two_columns_one_last]